It is late spring of 2015 and we are sitting in one of the most beautiful cities in Europe, talking about a grave violation of women’s human rights: violence against women. It has been a long time since I have been invited to speak about technology-based VAW to a group which primarily work in the area of women’s rights and VAW, but engages little, if at all, with internet rights. It is a mixture of politicians, police officers, government representatives, advocates, support organisations and academics.

Luckily, issues related to internet rights such as online harassment, anonymity and freedom of expression are not completely alien to them, as is sometimes the case when one speaks about VAW in tech-focused spaces. As I am listening to presentations and debates, I can see that this crowd sees different types of VAW, including online VAW, as part of the same continuum. In other words, as a “manifestation of the historically unequal power relations between men and women and systemic gender-based discrimination”. Here are several key points I took away from the Prague conversations:

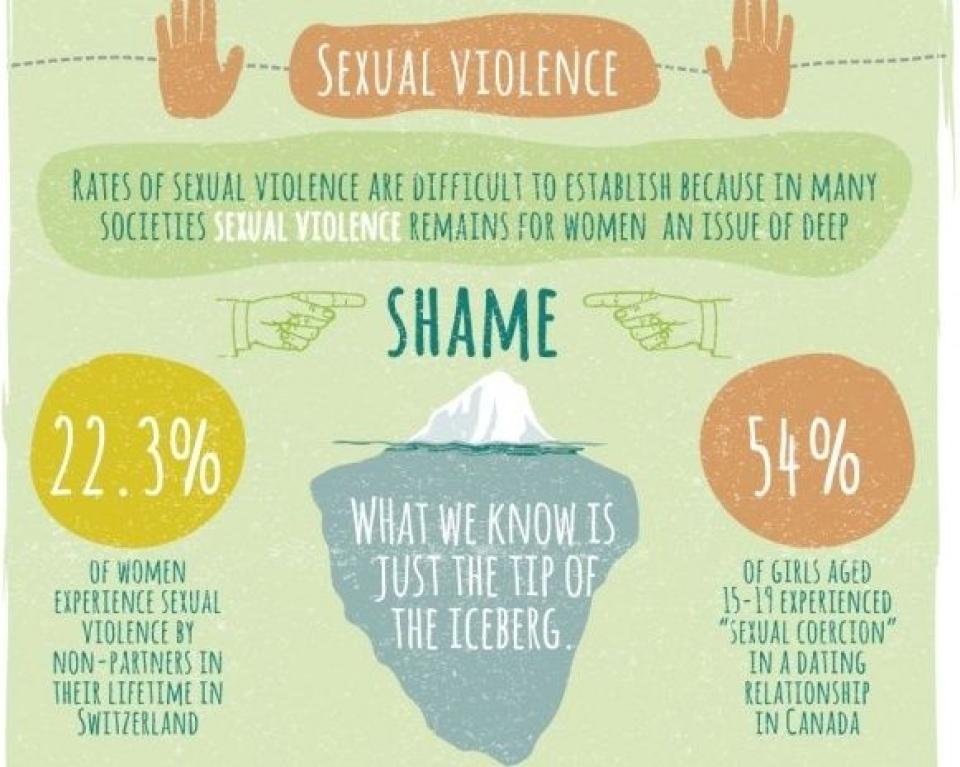

1) Reported cases are just snowflakes on the tip of the “iceberg” of violence against women

An image of the “iceberg” where cases of violence against women that we know about represent only the tip of it is very well known. The image illustrates the metaphor used to express that most of the cases are invisible to society.

However, I overheard in one of the panels that thinking about reported cases as the tip of the iceberg is too optimistic, and that in reality, the cases we know about are just snowflakes on this tip. This is certainly true for VAW online, and is definitely true from the findings of the APC Women’s Rights Programme’s Take Back the Tech! crowd map that collected testimonies of survivors of VAW online to make the invisible visible. Most of the mapped cases have been collected from the media, but only a few cases have been reported by the survivors themselves.

A vast majority of women who face VAW don’t go anywhere, they don’t seek any help, despite the harm and difficult situations that they are facing. One of the main barriers is a culture of shame that still surrounds VAW (sexual and intimate partner violence in particular). Paradoxically, this weight of shame lies on the side of the victims and not the perpetrators. It still takes a lot of strength and courage to stand up and say I was raped, I was harassed, I was blackmailed…

Anonymity and anonymous helplines are important for survivors of VAW. Anonymity provides them with the opportunity to share their story, to get information and advice, without having to openly face the culture of shame. Despite the internet often being glorified as the space for anonymity, survivors of VAW online have limited options on how to use it to their advantage, for reasons ranging from real name policies to the non-existence of anonymous reporting systems on social media platforms.

2) There is an inverse relationship between gender equality and violence against women in society

The fact that zero tolerance to violence against women goes hand in hand with gender equality in society was highlighted by various speakers. Gender equality is usually measured by the gender gap in education, economic participation and decision making.

Measured by the level of gender equality, we have a long way to go to achieve an information society free from VAW. The backstage of internet governance is occupied by white heterosexual men. IT companies and developers communities are well known for their weak gender balance and hostile environment towards women. Women and girls are marginalised in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Without systematically and holistically addressing the gaps in each piece of this gender inequality puzzle, including the availability of good quality ICT infrastructure for women, social media platforms will remain hostile towards women and continue to be a gallery of the worst gender stereotypes, sexism and misogynist speech.

3) Role of bystanders

Bystander initiatives are the primary prevention strategies that are being specifically used in the area of sexual violence and related forms of coercion. The bystander approach can also be very effective as a preventative strategy to address VAW online. In 2011, APC launched “the I don’t forward violence“ campaign calling for bystanders or witnesses of tech-based VAW to commit to not forward any form of message, video or photograph of someone being violated or humiliated.

The project presented by Klas Hyllander from MenEngage Europe takes the bystanders’ role a step further by turning them into “prosocial bystanders” who intervene against VAW. The prosocial bystander project mobilises prosocial behaviour on the part of potential bystanders by teaching them that if they step in against “lighter” forms of VAW such as jokes, gender stereotypes, objectification or degrading language, then other people are more likely to step in too. This is based on the understanding that since most people disapprove of VAW, they’re just waiting for someone to take the first step to stop it.

In an online setting, such projects specifically targeting social media users can be a promising strategy to counter a culture that is tolerant of VAW, which social media helps to perpetuate and facilitate at rapid speed. Similar projects already exist to prevent cyber bullying. Internet intermediaries in particular can play an important role to reach out to bystanders who witness VAW on their platforms.

4) The Istanbul Convention

My fourth take-away from the Prague meeting was the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, which was mentioned several times as a groundbreaking continent-wide tool to address all VAW in a holistic way. Primarily, the convention builds on the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and firmly establishes the link between the eradication of VAW and gender equality, setting a number of legally binding provisions that aim at advancing the status of women in society, such as to eradicate stereotypes, customs and prejudices based on the notion of women’s inferiority.

The convention sets out minimum standards related to 4 P’s – prevention, protection, prosecution and policies. Countries that ratify the treaty are not only obliged to protect and support victims of VAW, but also to address gender stereotypes and establish support services such as hotlines, shelters, medical treatment, counselling and legal aid. Among other things, the convention binds governments to develop a gender-sensitive asylum system that will include the right to international protection for women and girls who suffer from gender-based violence in third countries, if their own systems fail to prevent persecution or to offer adequate protection and effective remedies.

Article 17 of the Convention speaks directly to the role of internet intermediaries: “Parties shall encourage the private sector, the information and communication technology sector and the media, with due respect for freedom of expression and their independence, to participate in the elaboration and implementation of policies and to set guidelines and self-regulatory standards to prevent violence against women and to enhance respect for their dignity.” It also points to their role in increasing the skills of children, parents and educators to deal with “the information and communications environment that provides access to degrading content of a sexual or violent nature which might be harmful.”

The coming years will show if the promising forecast emerging from these two days of debates in Prague was right, and if the strategies presented will contribute to the melting of the “iceberg”.

Image source: Antonio di Vico

- 8460 views

Add new comment