In late 2014 the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) began publishing findings from our seven-country ‘From impunity to justice: Exploring corporate and legal remedies for technology-related violence against women’ research project, which included an analysis of Twitter’s reporting procedures. Case studies that involved abuse on Twitter and steps the company could take to improve the safety of their platform. Around the same time, the US organisation Women, Action and the Media (WAM!) became an authorised reporter on Twitter, which meant they could receive harassment reports directly from users and escalate them with Twitter staff. Over three weeks, WAM! received 811 reports, and they recently published what they learned in Reporting, reviewing, and responding to harassment on Twitter. The report is enlightening on its own, but it is especially useful as a companion to APC’s research.

Bystanders or delegates made 57% of the Twitter reports WAM! reviewed, while 43% came from the people who experienced the harassment. There are no demographics, but WAM! mentions that the project received exposure outside of the US, so some reports may have come from other parts of the world. Their reporting tool was only in English, however.

Hate speech and doxxing were the most common complaints, and ongoing harassment was a problem in nearly a third of the 317 cases WAM! deemed to be genuine harassment. Of these, WAM! escalated 43% to Twitter.

The company took action on 55% of escalated cases, either deleting, suspending or warning perpetrators, and the cases they chose to act on were typically associated with hate speech, threats of violence, or nonconsensual photography. Interestingly, Twitter was far more likely to act on doxxing reports than on violent threats, but WAM! suggests that this may have been due to the harasser’s ability to “tweet and delete” the evidence.

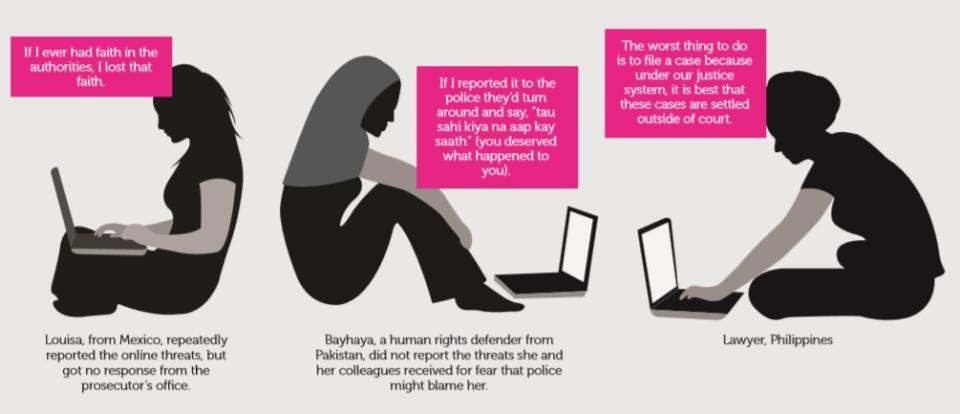

In line with APC’s research on domestic legal remedies, WAM! revealed that law enforcement often refused to take action and simply referred people back to Twitter. APC found that law enforcement frequently lacked the capacity to respond appropriately to cases. They refused to take technology-related violence seriously, blamed victims for the harassment and privacy violations they faced and failed to make use of available laws.

WAM!‘s discussion of common challenges to reporting makes a good counterpart to APC’s assessment of Twitter’s user policies and redress framework, because Twitter requires URLs as evidence and will not accept screenshots. Users cannot provide evidence when harassers delete their tweets or when reporting abuse that is not associated with a URL. WAM! describes first-time reporters as experiencing shock over the incident and confusion about how to report and especially how to find a tweet’s URL. These findings are a good reminder that violence against women that happens online causes real harm, and psychological ramifications combined with limited redress options can prevent users from successfully reporting.

A total of 17% of reports described harassment across several platforms at once, with Facebook being the most frequently identified additional platform. (In fact, APC’s Take Back the Tech! map of technology-related cases shows that Facebook is by far the most common social media platform where women experience violence, with Twitter coming in second.) There is no mechanism or procedure for multi-platform reporting, and there is no way to link multiple Twitter reports since each incident must be submitted individually. This mean Twitter’s reviewers are not seeing the whole picture, and the burden of filing report after report becomes, as harassers intend, “an extension of the harassment.”

Nearly one-fifth of reports were too complex to fit into one category, reflecting violation definitions that are too narrow or unclear. WAM! says that in order to fully respond to reports, platforms must put time and effort into navigating complex situations. In-depth conversation is sometimes necessary and can help establish trust and address the broader impact of harassment on the user. WAM!‘s findings on complexity and conversation resonate with APC’s research, which found that platforms often fail to understand the experiences of women outside of North America and Europe because reviewers lack understanding of important cultural nuances.

More than two-thirds of people in the 317 genuine reports said they had already notified Twitter at least once, and 18% said they had notified Twitter at least five times. As disappointing as these numbers may be, they are not surprising, as APC’s research discusses reports being rejected frequently. Likewise, WAM!‘s assessment of individual user safety sometimes did not match Twitter’s assessment, though WAM! suggests that authorised reporters are in a unique position to adequately assess risk. It may be that Twitter’s report reviewers need increased training on assessing individual safety and understanding the impact of psychological violence.

WAM! found that while authorised reporters can escalate reports, clarify the problem, provide emotional support and connect people to resources, there are concerns with this process. Twitter still holds the power since they choose authorised reporters and determine how the relationship works and how long it will last. Furthermore, authorised reporters may face the same mental health consequences as Twitter’s report reviewers and, presumably, without company resources for care.

Overall, WAM!‘s report backs up APC’s findings that companies like Twitter must do more to make their platforms safer and their reporting procedures more responsive. Now we wait to see what Twitter says it learned from the project with WAM! and what the company will do as a result.

Responses to this post

Thank you Sara. Great article. In relation to link multiple Twitter reports, one of the recommendation from APC’s report on corporate policies is to expand multiply strike policies, on which basis many internet platforms currently suspend accounts for copyrights violation, and implement them also for accounts that repeatedly harass, intimidate and/or abuse others, repeatedly create pages that get flagged and removed, or repeatedly post private information (including photos, videos or identifying information).

Also wonder how does one become authorized reporter?

- Add new comment

- 9397 views

Add new comment