Kenya was one of seven countries covered under the Association for Progressive Communication’s End violence: Women’s rights and safety online research project. Here, GenderIT.org writer Tarryn Booysen speaks to the research team, giving us a closer look into the research findings.

Tarryn Booysen (TB): Violence against women (VAW) often goes unreported. How did you identify the cases you mapped in the research and have you dealt with any difficulties in speaking to women about the cases?

Research team (RT): We identified cases from media reports, relatives who had experienced violence against women (VAW), and through the technology-related VAW training we carried out for women organisations. Yes a little bit of difficulty was experienced because tech-related VAW is a new form of violence unknown to most women.

TB: In the research report, Kenya has been rated quite negatively in terms of legal remedies to combat violence, what effect does this have on women who experienced technology-related VAW coming forward or acknowledging this as a form of violence and to what extent are the relevant authorities equipped to deal with various cases?

RT: Legal remedies were reported as a hindrance for redress mechanisms for women to seek justice. They cited lack of knowledge on tech-related VAW from law enforcers. Since the effect was more psychological than physical, the women interviewed chose to deal with cases internally instead of publicly, either through counseling services, or withdrawal from the use of social networks and not following up on a case reported to law enforcers due to long wait. Internet service providers too relied on police investigations regarding cases concerning them, and therefore did not deal with the customer complaints directly.

At the time of the research technology-related VAW was unknown even within women organisations dealing with VAW. Which is why they provided no redress for the women affected. But today relevant authorities are trying to address tech-related VAW by instituting laws that deal with cyber crime, for example.

At the time of the research technology-related VAW was unknown even within women organisations dealing with VAW. Which is why they provided no redress for the women affected. But today relevant authorities are trying to address tech VAW by instituting laws that deal with cyber crime, for example.

Legislation in progress:

1. The Constitution of Kenya is referred to closely in terms of human right needs – The Bill of Rights provides for the freedom of expression

2. Kenya has adopted UDHR, ICESR, ICCPR, Maputo Protocol, CEDAW

3. The Government has adopted the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights that ensures large share holders internet providers like Safaricom comes up with principles to protect customers directly.

4. The African Union Convention on cyber security and privacy, adopted the Data Protection in 2014.

5. The government is fighting VAW through existing institutions like Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), NGEC, IPOA, National Police Service (NPS), CID.

6. Sexual Offences Act – can be used on any harassment and sexual offences.

7. The Kenya Information Communication Act – deals with offensive communication, interception of messages and SIM registration.

8. The Penal Code deals with real space crime, criminal defamation, other physical offences – assault, threats of violence among others.

9. Protection Against Violence Act deals with various forms of abuse e.g. harassment, stalking, intimidation, committed by people in domestic relations. Also deals with all abuse, physical as well as emotional.

10. UN sustainable Development Goals – Goal 5 calls for elimination of all forms of violence against women.

11. There is proposed regulation under Kenya Information and Communication Act to deal with cyber security, child pornography, xenophobic attacks and consumer protection.

As a result, there are progressive tools and user policies on social platforms to deal with online VAW for example on Facebook, a subscriber has been given choices on who they want to add as a friend and whether one wishes to share with all etc.

TB: Based on the research findings, what changes would you like to see in next 2-5 years? Can you already list some impacts that have resulted from this work?

RT: In the next 2-5 years we hope to have law enforcers fully embrace online VAW as a crime and charge culprits according to existing legislation. We have been able to sensitize law enforcers on tech-related VAW with a view to reinforce gender desks which are functional. The enforcement of existing legislation is on-going and this has encouraged women to come forward when under attack.

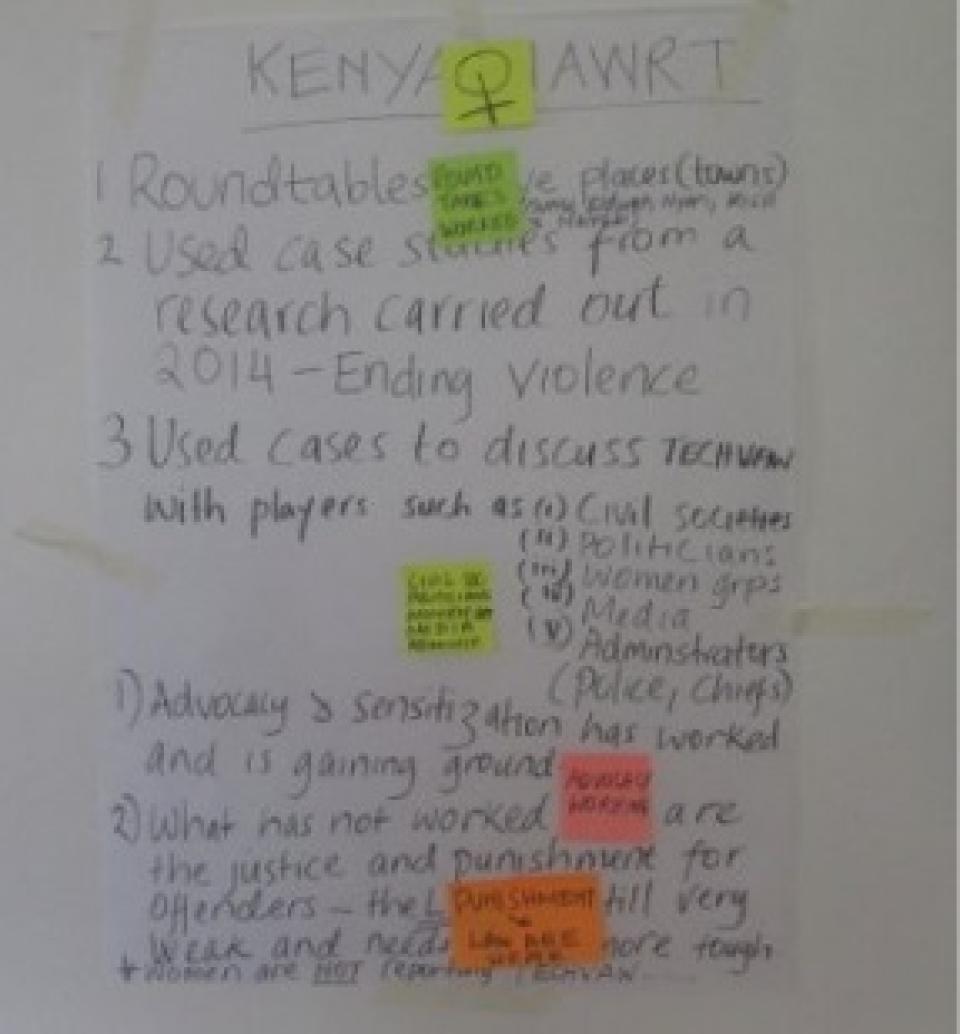

TB: Has the politics and awareness on the technology-related VAW improved at all over the last few years of the End violence project? If so, to what extent?

RT: There is a more public knowledge and an increase in discussion on and reporting of online VAW incidents. Evidence exists on the mapping of cases which have increased. The prosecution of hate speech via SMS by the National Cohesion and Integration Commission has further made the public more aware of such crimes.

TB: Your organisation works primarily with women journalists, how does technology-related VAW interests sit with media. Do you think they are more at risk to face violence because of what they do and what are the most common forms of VAW they are facing online?

Women journalists have been a major target of online abuse. Though our members are participating in tech-VAW activities, the larger constituency continues to face techvaw on various platforms. This is sometime in line with their work but in some cases, they are personal attacks on their person .

RT: Women journalists have been a major target of online abuse. Though our members are participating in tech-VAW activities, the larger constituency continues to face tech-VAW on various platforms. This is sometimes in line with their work but in some cases, they are personal attacks on their person. They are likely to face scathing attacks and rubbishing of their reports on Twitter; harassment and name calling. IAWRT makes a deliberate attempt to involve journalists of both gender from different media organisations spread out in different regions of the country.

TB: What role do you think media plays in addressing technology-related VAW? Do you engage with them around this topic?

RT: The media is fully engaged in informing audiences. The media is fully engaged in tech VAW, journalists map stories at county levels, they also report any activity on tech-VAW in newspapers, radio and television in as many languages as possible. Some produce programmes which are posted on Youtube. This has enhanced public awareness.

The research is also highlighting the role of the social media providers in relation to technology-related violence against women and it has become quite the topic of debate over last two years.

TB: What has been the response of local ICT companies? How do you see their role?

RT: The internet service providers, for example Safaricom, are making an effort to address customers directly by providing information that can help a complainant of certain service delivery. For example the company can provide abusive data in their custody that the police can use to prosecute a culprit. Such responses can be useful in curbing cases of mobile/online abuse because people become aware of legal implications.

The government through ICT Authority has a master plan that focuses on ICT and Information Empowerment. This has been addressed through the supply of infrastructure (laying of optic fibre for internet accessibility) and other phases to follow are demand/content. ICT Authority intends to de-masculinize ICT so that more women are encouraged to receive ICT education and also engage in ICT innovation for awards. This can further be enhanced by availing the right information for women online.

Organisations like Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTAnet) are advocating for IT to be made relevant to the needs of women and the mainstreaming of gender issues in ICT policy.

Organisations like Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTAnet) are advocating for IT to be made relevant to the needs of women and the mainstreaming of gender issues in ICT policy. As a catalyst for reform in the ICT sector in support of the national aim of ICT enabled growth and development, KICTAnet believes increased access to broadband will translate to increase in use of ICTs and the Internet in particular. It has therefore become very urgent to ensure that policy and regulation is developed to address issues of cyber violence against women.

This statement is part of research on Gender Research in Africa into ICTs for Empowerment, which attempts to provide an evidence based framework to address cybercime against women in Kenya.

This research is part of APC’s project “End violence: Women’s rights and safety online”, financed by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS).

For more information about the multi-country research visit the research site

- 7674 views

Add new comment