Original illustration by Neema Iyer for this edition of GenderIT. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

The saying “we live in interesting times” has never been more true than it is now. With the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the novel coronavirus, Covid-19, a global pandemic, most news outlets and the internet are flooded with both information and misinformation about the virus, how it’s contracted, how it’s spread and how people can protect themselves and their loved ones from contracting it. I too find myself lost in various wormholes of information and updates about the virus, as I worry about my loved ones, friends and workmates scattered across the world. In this time of self and enforced quarantine and isolation, the internet and other communication technologies have become a lifeline for many people.

With many gatherings and meetings being cancelled and postponed, the quick and easy solution that is being shared around is “well then, let’s just meet online”, and therein lies the problem: presenting the internet as a solution to a social problem, as some kind of communication silver bullet that imagines an equality of access, use and representation on the internet which is false. And this is why we need even more African feminists and feminisms on, in, around the internet, to counter the idea that technology somehow levels the playing field for all, and is an infallible solution to all our problems.

What does the current Covid-19 global crisis have to do with a gathering of activists in Africa to “make” a feminists internet? A lot in fact. When the All Women Count-Take Back The Tech! (AWC-TBTT!) project at the Association for Progressive Communications Women’s Rights Programme (APC WRP) decided to host a Making a Feminist Internet in Africa and the Diaspora (MFIAfrica) gathering in October 2019, the goal was clear. Find and bring together as diverse as possible a group of African activists, thinkers, artists and feminists to talk about technology, the internet and the power and impact it has on our lives and our work. This was not the first gathering of its kind, but it was the first such gathering held in Africa, with and for African feminists and activists.

We need even more African feminists and feminisms on, in, around the internet.

These gatherings started in April 2014, when the WRP, already curious about and working on technology and its effect and role in shaping the lived realities of women, LGBTIQA people, people with disabilities and the collective of people who exist on the margins of normative societies, called a meeting of minds and ideas to explore what a feminist internet can look like. What came from this meeting was the first draft of the Feminist Principles of the Internet (FPIs), a working and evolving feminist analysis and understanding of the role of the internet and technology in our lives. There have since been many more such MFI gatherings in East Europe, South America, Southeast Asia, Asia and more recently Africa.

Since the first Imagine a Feminist Internet meeting in 2014, a lot has changed in the technology and internet landscape all over the world. In Kenya, for example, between 2015 and 2019, active internet use in the country increased by 15 million users. This change in numbers is most visible on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, with a few more women’s voices, more (although not enough) visibility of LGBTIQA people and more African voices setting old and current scores straight online. This has also become visible because of the increased incidence and reporting of gender-based violence online and technology-assisted violence. The speed of changes in technology significantly affects how our societies function and evolve. Technology has thrust communities of people online and offline into a space where the online realities and emerging issues do not have offline processes and recourse. Online gender-based violence, for example, has been a pressing concern raised by many women, LGBTIQA and gender non-conforming people, but legislation that recognises and acts on these attacks and violence is largely absent in many African countries. Because of this, the online space has become a “safe space” for people and communities of people to attack women, LGBTIQA people and enbies and mostly get away with it. This bridging of our understanding and learning around how inextricable our online and offline lives and realities have become remains important work that the WRP and thousands of other activists and present voices online continue to do. In many ways, the internet feels like a brave new world that is in danger of mirroring oppressive norms and ideas that have existed in the unequal world we have lived in. The inequality of access to and representation on the internet is fast replicating existing oppression and suppression. Africa’s particular voice and history in this dynamic needs to be a loud and powerful narrative that shifts the dominant white tide towards a different and more inclusive internet.

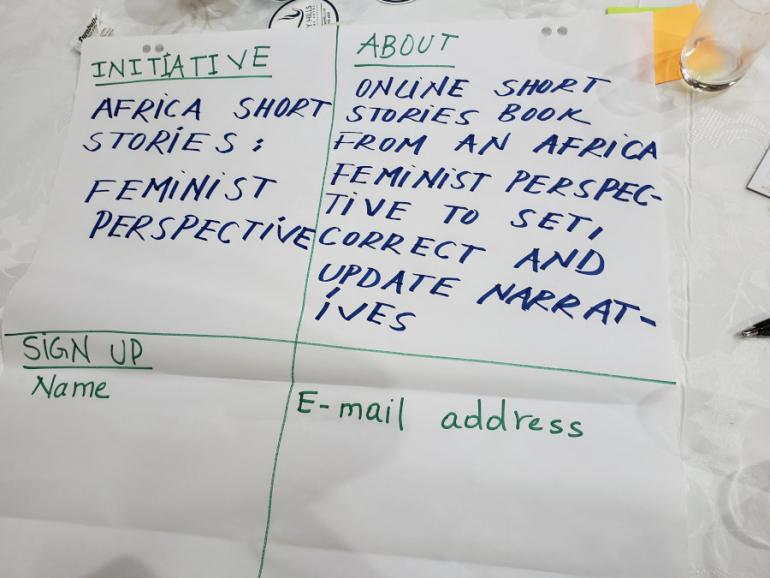

A paper to sign up for one of the participants initiatives shared at MFIAfrica: "Online short stories book from Africa feminist perspective to set, correct, and update narratives." Photo by Fabiola Ingabire.

The inequality of access to and representation on the internet is fast replicating existing oppression and suppression. Africa’s particular voice and history in this dynamic needs to be a loud and powerful narrative that shifts the dominant white tide towards a different and more inclusive internet.

Africa, since its advent, both as a Western colony and as a continent independent of visible colonial structures of power and oppression, has been a curious case study for the world. Many times, Africa feels like the word’s laboratory, and many times it has been treated as such. Our continent is the space where Western pharmaceutical companies come to test drugs illegally. This happened in the northern state of Kano in Nigeria, when the global pharmaceutical giant Pfizer illegally tested an anti-meningitis drug on children that caused their disability or death. The continent is littered with such stories of rampant disregard for the lives and environment of Africa and its inhabitants.

When it comes to our interactions with technology, Africa is often positioned as a beneficiary of technology, not an innovator of it. In addition to this, the many innovators and thinkers of technology are often pigeonholed into innovating and creating around existing problems on the continent. Our innovations are responses to famine, drought, disease and death. Technology in Africa is something that we use to change our lives, we do not innovate for fun, for pleasure and for play. This is a generalisation of course, but also, this is the dominant narrative you will find online. This is the danger of a single story that Chimamanda speaks of, where multiple truths are treated like water and forced to take the shape of the vessel they are poured into.

In the dark corner of the popular narratives of Africa and its people (and problems) you will find shelved the stories of women, queers, and people with disabilities. We live a layered and complex reality where we have not always been the custodians of our narratives. This invisibility of African narratives and realities trails after Africans living in the diaspora, with a commonality of experiences shared across the continental border and over centuries and decades. But this is shifting, and we have African feminists to thank for this.

Technology in Africa, is something that we use to change our lives, we do not innovate for fun, for pleasure and for play. This is a generalisation of course, but also, this is the dominant narrative you will find online.

The internet and technology are a powerful space, I daresay force, that African women and LGBTIQA people have always contributed to. Our everyday lives extend to online platforms and tools where we plan and share and love and grow. The internet has helped shape how we are perceived and how too we perceive ourselves. The internet is also a site of great violence that is directed at people who express themselves in ways and voices that do not conform. For the days during the Making a Feminist Internet in Africa gathering, women, queer and non-binary folx, artists, writers and researchers (just to name these few) from Africa and the diaspora created space to talk about a feminist internet and what it would mean for movement building in Africa. In this space we found a commonality of not only struggles, but triumphs. We shared tactics and ideas, we even shared our music and dances! For all the homogeneity that Africa is presented as, we don’t know enough about each other and we are divided by history, language and political strain. A lot of news and information is controlled by media monopolies, that operate in the shadow of Western media houses that most times are better resourced and are able to access stories and shape narratives that despite us living on the continent we cannot access. What we see in the media is many times what we take as truth. We sit with many misconceptions about each other, and about our realities. Africans in the diaspora in particular don’t easily fit into stories and narratives about Africa and Africans. The internet has created (sometimes contentious) spaces for these conversations.

Having over 40 feminists and activists from all over Africa in one room, made us aware of our own judgements, privilege and power in the face of various national and regional struggles. In the room, it became clear that the internet as it is, is as unequal as the world we live in. The same kind of kindness and care that we move in the world with when trying to understand the various problems that we live with, is needed online. But for this to happen we need more African feminists taking up space, telling stories, giving alternative views, creating body-positive content, showing off our bodies and talents and skills. African feminists make more room for African women online. The power of finding stories by queer Africans talking about their dating lives under the gaze of oppressive and suffocating social and cultural realities, is critical. Finding fashion content for fat women, sex and sexuality content for women and LGBTIQA people with disabilities, make-up content for gay boys, is resistance made visible. The internet reminds the heteronormative status quo that we will not disappear.

...we need more African feminists taking up space, telling stories, giving alternative views, creating body positive content, showing off our bodies and talents and skills. African feminists make more room for African women online.

We are still missing many stories and realities of African women and LGBTIQA people online. A feminist internet must have more African women, more sexuality and diversity, more glitter and ochre. A feminist internet does not invisibilise the contributions of women and Africans to developing technology and shaping various aspects of the internet. At a time when the most vulnerable people are being asked to stay away from others, we are turning to an internet that is bigoted, racist, homophobic and classist for company and connections with a wider world. We are asking people that do not have meaningful access to the internet to work from home on connections and technology that they don’t have. We are forcing people to turn to an internet that does not have enough information about how to show care for those affected by the epidemic. Without enough voices of reason and care for difference and diversity, we are in danger of people emerging a month after quarantine more conservative and more radicalised than before, through accessing an internet that represents a dominant and oppressive minority. Without a feminist internet that ensures that all people can access and influence content and governance of this internet, we will be replicating a violent and oppressive way of life that might eventually be inescapable.

A feminist internet with more African voices is also a vibrant space. A space to play and a place of pleasure. Making a feminist internet is more than just a gathering of like minds, it is also a call to action. It is a demand for diversity, and safety and fun. It is a big ask. But one gathering at a time, like the Making a Feminist Internet in Africa meeting, it is possible to begin to push for the same kinds of social, cultural, economic and political changes online that we demand offline/onground. In this global moment of crisis and isolation, the need for a feminist internet, one that includes and centres the voices of African feminists, is no longer necessary, it is crucial.

- 14994 views

Add new comment