Footnotes:

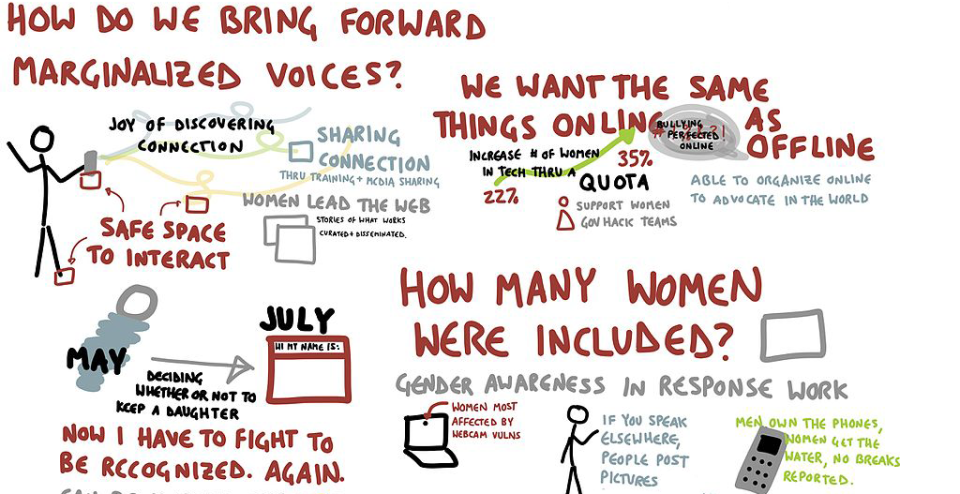

Image from original work ‘Web Women Want’ by Willow Brugh. Licensed under cc-by-sa-2.0.

There were countless reasons for a young, Malaysian feminist, internet rights activist, to be excited about RightsCon Brussels. Not least because Belgian waffle is the bomb, but I craved the adrenaline rush of compelling, inquisitorial and powerful discourse on human rights, gender and technology; the sort of interactions that would inspire and spark new perspectives, new ideas, and new friendships.

The programme

More than 1,500 business leaders, civil society advocates, policy makers, lawyers, bloggers, technologists, and users participated in RightsCon Brussels, which took place from 29 – 31 March 2017 at Crowne Plaza Brussels Le Palace. There were more than 250 sessions on the most pressing issues at the intersection of technology and human rights.

A programme track system was introduced by the organiser, with the intention of helping attendants to navigate around all the sessions based on a specific theme, from start to finish, from diagnosing the problem to identifying best practices and solutions. Or you could jump around the programme and pick whichever session to go to. This is a brilliant idea, and many people I spoke to at the conference found it useful.

Freedom of expression for all, not few

It is heartening to find that the two gender-centred sessions “The Four Finger Rule: The Impact of Sexuality Censorship on Society” and “Are Naked Bodies Harmful? Sex, Law and Digital Rights” were integrated into Track 02, “Freedom of Expression: WTF now?“. Yes, women’s and LGBTQ rights are human rights, period. It is not a battle to be fought alone by women, LGBTQ and sexual rights activists. A gendered analysis helps to unpack power relations in society and examine how each experiences violations and barriers to their freedom of expression differently. It is important to address the often “invisible” and systematic discrimination that would otherwise appear neutral. For instance, for men, these restrictions and persecutions tend to come from the government; women’s right to freedom of expression, on the other hand, are severely hampered by gender-based discrimination and violence. This was reaffirmed in the outcome document of Internet Governance Forum (2015): Best Practice Forum on Online Abuse and Gender-Based Violence Against Women, “…the fact that online abuse and gender-based violence acts to impede women’s rights to freedom of expression by creating environments in which they do not feel safe to express themselves needs to be included in these debates.”

The fact that online abuse and gender-based violence acts to impede women’s rights to freedom of expression by creating environments in which they do not feel safe to express themselves needs to be included in these debates: Best Practice Forum on GBV at IGF 2015

Framing exclusion and marginalisation

And then there was Track 07, “Empowering At-Risk Communities: LGBTQ, children, refugees, and women“. The title of the track disconcerted me. It is not uncommon to come across conferences where different groups are categorised as “at-risk”, “marginalised”, or “vulnerable” communities. While a dedicated track may appear to give the necessary focus and attention on the human rights issues faced by these groups, it can also serve to further marginalise them and place them on the periphery of the so-called larger issues. It does not help to foster cross-understanding between the many actors and players at RightsCon.

Oppression rarely happens on the grounds of one factor at a time. Our experiences are a confluence of interplaying identities linked to gender, ethnicity, religion, race, sexual orientation, disability, national origin, age, etc. And together they produce uniquely felt experiences of exclusion, resulting in multiple grounds of discrimination. While transgender women face political, social, and economic discriminations in their everyday life, their experiences may differ from Muslim transgender women, located in a country with a Sharia legal system.

An intersectional approach to understanding discrimination would reveal the complexity of how people experience discrimination, and would take into account the historical, political, economical and social context of the group. As written by Kimberle Crenshaw,

p((. “intersectional subordination need not be intentionally produced: in fact, it is frequently the consequence of the imposition of one burden that intersect with pre-existing vulnerabilities to create yet another dimension of disempowerment.” [1]

The missing Indigenous women in Malaysia

One example of this kind of structural intersectional discrimination would be the issue of indigenous women in Malaysia, who remain a predominant percentage of the unconnected population in the country. Policy and development strategy on access tend to view access as a mere technical and infrastructure solution and overlook the barriers of cultural and social norms that hinder indigenous women from benefiting from technology. This includes

- traditional care responsibilities that take away their time from exploring the internet;

- higher illiteracy rate among indigenous women and language issues;

- and lack of disposable income and financial resources to afford devices, data packages or to pay for public access.

Social-welfare policy implemented through e-government system, or international trade agreement that favour ecommerce or integration of ICTs in certain geographical area would, by default, exclude the most oppressed groups in society. An internet without net neutrality would disproportionately affect and exclude the indigenous women from accessing a free and open internet, who are already straddling on the fence of economic inequality. They are also burdened by social media’s anathema to privacy, especially when their photos and information are shared in the absence of their explicit consent and in some cases, sexualised or misrepresented as vulnerable and needing charity. And then there is the big bad wolf – the big data.

The indigenous communities in Peninsular Malaysia make up less than 1% of the entire population in Malaysia, and they are largely missing across all major decision-making positions. Big data often omits the experiences of indigenous communities whether due to geographical factor, existing lifestyle, poverty or lack of access to ICTs; whose lives are misrepresented or missing from the public sphere, or not regularly harvested or “datafied” than the general population.

Big data often omits the experiences of indigenous communities whether due to geographical factor, existing lifestyle, poverty or lack of access to ICTs; whose lives are misrepresented or missing from the public sphere, or not regularly harvested or “datafied” than the general population.

The risk of algorithm discrimination is succinctly explained by Dr Nicole Shephard,

“… accept that the work and infrastructures involved in collecting, storing, and computing data are never neutral but manmade (pun intended) and embedded in power relations, it might go without saying that questions of privilege extend to data and the politics of algorithms in more ways than one.”

All of this shapes the exclusions, struggles and discriminations of humans in ways that can never be captured wholly by further compartmentalising those disempowered and putting into categories of people who are marginalised. It requires all of us – the business leaders, civil society advocates, policy makers, lawyers, bloggers, technologists, and users – to take a closer look at the existing systems of power and ask the tougher questions: who is designing and running the system? Who is benefiting from it? What is the value we are bringing into the society? Who are we? Who are they?

Transforming gender politics, patriarchal and capitalist values with ICTs

This is an exciting time to be alive and breathing. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) could be a powerful tool to transform gender politics, to disrupt systems built based on patriarchal, elitist, non-democratic and capitalist values. And that potential can only be realised if the gender dimensions and intersectional approach are properly understood and adequately addressed by all stakeholders across all sectors.

Across the world, women and girls are using ICTs to advocate for their fundamental rights to health care, abortion, education, political participation, access to justice and more; to rewrite and correct the false narratives on feminism, gender identity and sexual orientation; to challenge existing and emerging barriers to women’s voices; and to stand in solidarity for the human rights movement collectively, while acknowledging the strengths in our diversity. Such was my main takeaway from the session on “Feminists Taking Over the Web Using ICTs”, organised by Hidden Pockets. An abundant amount of initiatives, ideas, best practice and strategies were shared and discussed by panellists, and actively joined by participants who have had similarly used ICTs for social, political and economic participation.

In a separate session titled “Your Algorithm Can’t Contain Us! Period Trackers in the Developing World”, organised by Coding Rights, Hamdam a period tracking app in Iran, was designed as an alternative to existing apps that are anathema to users’ privacy and comes with deplorable data protection policy. In addition to being an open source app, Hamdam is equipped with Jalali calendar and provides a database on sexually transmitted diseases, breast cancer, domestic violence, rape, divorce and division of assets, employment – issues considered largely taboo in Iran cultural context. Access to such information is pivotal so that women take control of their bodies, remained informed of their rights in marriage or/and in society.

Similar, a digital story map was used by the Sarayaku communities in their path to justice. Shared with us in the session titled “Mapping Land Rights: Using Technology to Protect the Living Forest With The Sarayaku Community of Ecuador”, by Center for Justice and International Law, the map was created to capture the story and struggle of the Sarayaku and to highlight how the Ecuadorian State parcelled off even more of their territory to oil companies despite the favourable judgment to the community by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2012.

A sobering reminder from a fellow feminist

I must also not forget the many interesting exchanges and conversations I have had with different people over coffee, wine and meals. A particular conversation with one of my favourite feminist friend lingers in my mind since then, “by the time we find a solution to connect everyone to the internet, the richest of the rich would have migrated to another planet”. I laughed, bitterly. I can’t remember what exactly followed in our conversation, but I still left feeling encouraged and inspired by our conversation. Yet her words are a sobering reminder of why we are all in this journey.

Today, RightsCon, or any other internet governance and human rights spaces, we desperately need more people, regardless from which sector, who will challenge the current power structures; to speak to the needs and realities of women in all our diversity; to reclaim technology as a space for empowerment, not for few, but for all. Now, I am excited about integrating these newly gained knowledge and inspiration into my organisation.

Today at RightsCon, or any other internet governance and human rights spaces, we desperately need more people, regardless from which sector, who will challenge the current power structures; to speak to the needs and realities of women in all our diversity; to reclaim technology as a space for empowerment, not for few, but for all.

Footnotes

1. Crenshaw, Kimberle: Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review Vol. 43, July 1991.

2. Nicole Shepherd, “Algorithmic discrimination and the feminist politics of being in the data”, GenderIT, 6 December 2016 http://www.genderit.org/node/4864

- 5501 views

Add new comment