The women’s movement in Africa should up the ante in its fight against the male-dominated, hyper-masculine policy and legislative development framework that has tended to exclude women in cybercrime and cyber-security debate leaving them victims of abuse.

The sharp rise in technology-related violence against women and its normalization has made the use of the internet a gendered issue. Therefore it has, of necessity, become imperative that women got to the fore of the debate on cyber-security instead of leaving it solely to governments and the financial/business sector as is the case in national and regional governance forums.

A recent baseline report by the Media Foundation for West Africa on the challenges faced by Ghanaian women on the internet indicates that online harassment hinders women’s full participation. The report lists non-consensual distribution of intimate images, sexual harassment, stalking, hate and offensive comments as the most prominent violations.

Women’s online sexual harassment, surveillance, unauthorized use and manipulation of personal information, including leaked images and videos, are a prominent feature on the African cyberspace. In most cases the harassment takes both subtle and blatant sexist or misogynistic approaches, which often develop into physical or sexual threats.

Women’s online sexual harassment, surveillance, unauthorized use and manipulation of personal information, including leaked images and videos, are a prominent feature on the African cyberspace.

I have keenly monitored this trend in what still remains, a week later, a highly charged election in the southern African country of Zimbabwe. Despite that women in the country made up over 50 percent of the registered voters who cast their ballot on 30 July 2018, they continued to be treated as second-class citizens in the digitally evolving public sphere.

Access to the internet, and particularly social media, changed the ball game in this election. It presented the candidates with greater reach for their messaging and, the electorate for the first time, had direct access to the candidates and also the opportunity to engage among themselves. However, structural sexism and misogyny continued to rear their ugly heads impeding women’s enjoyment of their civil and political rights in the election.

This has tended to be the trend across Africa today.

Structural sexism and misogyny continued to rear their ugly heads impeding women’s enjoyment of their civil and political rights in the election.

In 2016 a study by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), indicated that online societies judge women politicians more harshly than they do male politicians. The study noted that on social media women politicians were at the receiving end of sexist comments – with their appearance and marital status often being the subject of discussion in gauging their ‘fitness’ for public office.

For Zimbabwe, not only did the political parties fail to meet the gender quota for the parliamentary and local government contestants but also, women were generally disenfranchised. Internet access and use, it would seem, has extended the perpetuation of psychological, emotional and highly sexualized violence against women thereby reinforcing patriarchal prejudices based on culture and religion. Throughout Zimbabwe’s pre-election period, we witnessed an upsurge in attacks against women in public office, running for election and those seeking to exercise their democratic right to public space.

Internet access and use, it would seem, has extended the perpetuation of psychological, emotional and highly sexualized violence against women thereby reinforcing patriarchal prejudices based on culture and religion.

On her Facebook page, former Vice President of Zimbabwe, Joice Mujuru, who ran as one of the four female presidential candidates was often referred to derogatively as Mbuya (hag) despite that the country’s president-elect, Emmerson Mnangagwa was thirteen years older but his age never became an issue in comparison to hers.

Following the wrangle for the leadership of the Movement for Democratic Change Alliance between Nelson Chamisa and Thokozani Khuphe after the death of Morgan Tsvangirai, the founding president, the latter became a target of abuse simply because of her gender. Following Tsvangirai’s demise in February, Khupe as vice-president was the natural successor but she was elbowed out on sexist grounds. Not only was she attacked on her Twitter handle, @DrThokoKhuphe, but also on comments on popular online news platforms such as Nehanda Radio and the Voice of America.

Despite the apparent reality of Khuphe’s lack of popular support, given her 0.9% showing in the presidential election, she continued to be victimized for the loss of rival party MDC Alliance. A Facebook post by senior journalist, John Mokwetsi which read, ‘I am happy that Khupe is now sitting at home with no relevance. Good riddance,’ attracted derogatory labels such as ‘bitch’ and ‘fool’

Screenshots. Image source:author

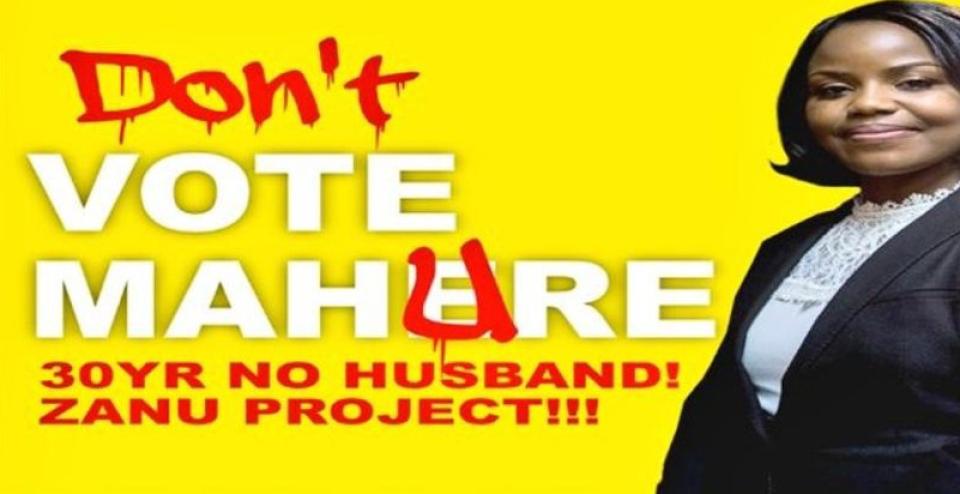

Young and independent female parliamentary aspirants also received a fair share of the slander, with defaced posters of candidates Fadzayi Mahere and Paidamoyo Nyamakanga.

Screenshots. Image source:author

In both posters they were – in similar fashion – said to be ‘whores’ or women of loose morals. Mahere was on several occasions reminded on Twitter that she was single and should marry and begin making babies instead of vying for public office.

Similarly, feisty human rights activist, Linda Masarira, who joined the Khupe faction of the MDC, was on several occasions reminded she was ugly and the paternity of her children was brought into the public arena.

In both posters the women politicians were – in similar fashion – said to be ‘whores’ or women of loose morals.

Though there was much ‘excitement’ over a tweet by former state newspaper editor, Edmund Kudzayi, in which he alleged that Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) Chairpersion, Justice Priscilla Chigumba was having an affair with former Mines Minister, Winston Chitando, it never came as a surprise. The tweet noted that the alleged affair posed a ‘conflict of interest’ because if the ruling Zanu PF party lost the election, then her lover would lose his job. It was a push to have her resign.

Interestingly, whereas online violence against women is usually perpetrated by men, who over the past year have ganged up or trolled women who dare speak out, women themselves have become, in some instances, agents of patriarchy perpetrating violence against other women on social media.

Women themselves have become, in some instances, agents of patriarchy perpetrating violence against other women on social media.

The #ChigumbaChallenge, which ensued a day after the announcement of the presidential election results, is a case in point. The challenge, in the form of pictures ridiculing Chigumba’s makeup, leaves one wondering why women revert to this kind of dark humour, especially where women’s capabilities are questioned.

Screenshots. Image source:author

This trend replicates itself for the most ordinary Zimbabwean woman who dares speak up openly against popular opinion or turns down sexual advances or leaves a relationship/marriage.

While the response of Zimbabwean feminists especially to the use of the term ‘hure’ (whore) on social media has been to appropriate it with the hashtags, #ProudlyHure and #MahureRUs, that falls short of a robust response. Labels are used to continually discredit and divide women on morality grounds defined by culture and religion and yet all the while entrenching patriarchy. Women should begin to challenge the cultural and religious mores promoting the prejudices against them.

Labels are used to continually discredit and divide women on morality grounds defined by culture and religion and yet all the while entrenching patriarchy. Women should begin to challenge the cultural and religious mores promoting the prejudices against them.

These prejudices hinder women’s participation in the public discourses and processes as they cower, self-censor and, in some instances, totally withdraw. Until there is recognition that such abuse of women on cyberspace are, in fact a cyber-security concern with serious impact on women’s participation, policy debates would not balanced.

The reality, however, is that women must stand up and ensure that they are a part of these policy discussions. The recommendation by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Online Violence Against Women, Ms Dubravka Šimonović at the 38th session of the Human Rights Council emphasized the responsibility that states and internet intermediaries have in dealing with the extension of systemic structural discrimination and gender-based violence against women on the internet.

The recommendation by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Online Violence Against Women, Ms Dubravka Šimonović at the 38th session of the Human Rights Council emphasized the responsibility that states and internet intermediaries have in dealing with the extension of systemic structural discrimination and gender-based violence against women on the internet.

The labeling, shaming, intimidation, degradation, belittling and/or silencing of women by making reference to their bodies, past and present sexual relations and marital status is criminal.

- 70 views

Add new comment