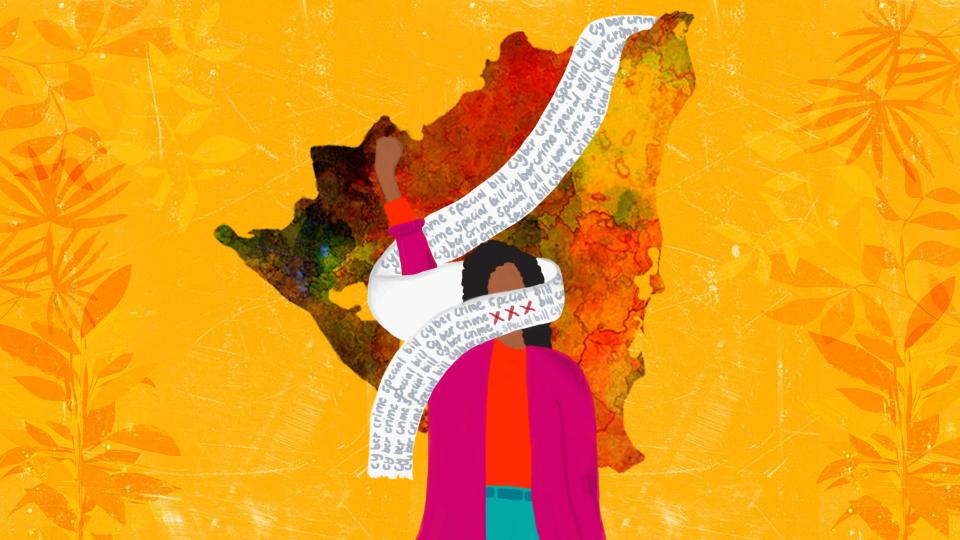

Illustration by Paru Ramesh for GenderIT

Nicaragua has a complex and cyclical history of using censorship as part of a state strategy to control and criminalise individuals and media outlets critical of the abuse of power. The Black Code [1], during Somoza's dictatorship, and the actions carried out by the National Media Direction [2] during the 1980s, are the closest precedents.

Over the past 12 years, social mobilisation has succeeded in halting legislative initiatives that threatened freedom of expression. These initiatives were promoted at critical moments in the political debate on extending the rights of women, children and young people. Appeals were made for their protection, progress or 'for the good of the family', a rhetoric that called for control and surveillance to guarantee security. Historical demands of social movements were co-opted to justify undermining other fundamental rights.

Special Law on Cybercrime: A Gag on Freedom of Expression

On 28 September 2020, the draft Special Cybercrime Law was presented to the Nicaraguan National Assembly through the Justice and Legal Affairs Committee. It was voted on 27 October 2020, with a parliamentary majority: 70 members in favour and 16 against. The explanatory memorandum preceding its presentation explained that this law was "highly specialised and technical" and that special attention had been paid to definitions. It also stressed the international nature of cybercrime, which is why this law would punish crimes committed inside or outside Nicaraguan territory.

This bill caused immediate national and international outcry due to its ambiguity in the definition of new punitive typologies. At the national level, the media and independent journalists were the first to identify these new crimes as an attack on freedom of expression and freedom of the press and named it the Gag Law. It was also soon criticised by civil society, which pointed to the risk it posed to social movements, independent media and dissident voices. The Foundation of former president Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, committed to the defence of freedom of expression and the promotion of investigative journalism, spoke out at the time, stating that it criminalised the possibility of freely expressing ideas through social media, especially those critical of public administration [3].

At the global level, APC reported that the initiative exalted "censorship, seeking to avoid public scrutiny and silence legitimate expressions, including criticism"; IPANDETEC claimed that "it was a deficient legislation, which did not incorporate previous studies of incidence and demonstrated a lack of knowledge of the phenomenon of cybercrime in the country"; Access Now, drew attention to the fact that one of the most significant flaws of the law was the fact that "Nicaragua is not a signatory to the Budapest Convention, so the proposed law is not in line with international agreements and pacts that regulate cybersecurity"; Derechos Digitales, noted that "the creation of a legal tool that allows the establishment of an arbitrary system to control the flow of information is particularly alarming".

The Most Problematic Elements of the Law

The Special Law on Cybercrime comprises 48 articles distributed in 8 chapters. Of 31 newly established crimes, 30 are punishable by prison sentences. Discussions in the approval process focused on affirming that the law was designed to protect children, women and the "Nicaraguan family", understood as vulnerable sectors of society. According to Walmaro Gutiérrez, MP for the ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) party, accused those who were against the wording of the law of "wanting to continue to promote hatred, disinformation, destruction, terror and death".

Chapter 5, for instance, details crimes related to sexual freedom and integrity, punishing anyone who involves children, adolescents and persons with disabilities in pornography or who uses technology to abuse them. This chapter also defines harassment and sexual harassment enabled by ICTs. However, these crimes that refer to minors reaffirm what is established in the Nicaraguan Children's Code and the Nicaraguan Penal Code. And the crime of sexual harassment is complemented by the provisions of Law 779 against violence against women.

Articles 7 on improper surveillance of communications, 22 on impersonation, 26 on improper disclosure of personal data, 28 on threats through technologies and 29 on incitement and inducement to commit crimes can be legal remedies used in cases of women experiencing digital violence. At a glance, we could assume these articles could offer protection to women facing gender-based violence online. For example, that was the case of Salma Floresi, a renowned Nicaraguan digital celebrity who brought a lawsuit against Kevin Alexander Reyes Leyton, her ex-partner, for disclosing an intimate video without consent. Reyes Leyton was sentenced to 5 years for improper personal data or information disclosure. However, there is uncertainty about the extent to which the law is being applied in such cases. This conviction is suspected to be related to the degree of public exposure the case took.

The most problematic article of the Special Law on Cybercrime is Article 30, on spreading fake news through digital technologies. It states:

"Whoever, using information and communication technologies, publishes or disseminates fake and/or misrepresented information that causes alarm, fear or anxiety among the population, or a group or sector of the population, or a person or their family, shall be sentenced to two to four years imprisonment and a fine of three hundred to five hundred days' imprisonment.

If the publication or dissemination of the false and/or misrepresented information damages the honour, prestige or reputation of a person or their family, a penalty of one to three years imprisonment and a fine of one hundred and fifty to three hundred and fifty days' imprisonment shall be imposed.

If the publication or dissemination of the false and/or misrepresented information incites hatred and violence and endangers economic stability, public order, public health or sovereign security, the penalty shall be three to five years imprisonment and a fine of five hundred to eight hundred days' pay".

What legal parameters determine that a population, a person or a family feels alarm, fear or anxiety? Who determines the honour, prestige or reputation of a person or their family? What characteristics should a piece of information have or lack to be considered false or misrepresentative?

In the document Considerations to the Special Law on Cybercrime, published by the Human Rights Collective Nicaragua Nunca+, the article is specifically analysed, and attention is drawn to the discretional nature of its application. "This offence is perfectly applicable to a large number of cases and information disseminated; its breadth, lack of clarity and discretion makes it impossible to be certain when this offence is committed", they conclude.

Criminalising Women Human Rights Defenders Under Special Cybercrime Law

"In a context of repression, violation of human rights, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom of association. This law, being born in this context, is a clear sign that what is intended is to instrumentalise the legal framework and criminal law to eradicate dissent," lawyer Maria del Socorro Oviedo Delgado told the Esta Noche T.V. show on 22 July 2021 about the Special Law on Cybercrime [4].

Based on these statements, Maria Oviedo was arrested a week later and prosecuted two months after that. She was convicted and sentenced to 8 years in February 2022 for conspiracy (sentence of 5 years) and spreading fake news (sentence of 3 years). As part of the Permanent Commission for Human Rights (CPDH) team, María Oviedo's work was publicly visible. On a previous occasion, she had already been detained for three days while defending herself against a police attack. Oviedo was the first woman defender to be convicted under this law.

A few months after this incident, around the presidential elections of 7 November 2021, in which Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo were once again irregularly re-elected, mass arrests were reported against people who used their social networks to protest against irregularities in the electoral process: defenders Nidia Barbosa, Evelyn Pinto and Samantha Jirón, the regime's youngest political prisoner when she was arrested at the age of 21, were among them.

Nidia Barbosa, a lawyer and activist from the department of Masaya, aged 66 at the time of her arrest, is a member of the Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy. This opposition group was organised following the civic uprising of 2018. She was convicted in February 2022 and sentenced to 11 years in prison and a fine of 800 days, meaning she would finish her sentence at 77. During the appeal process, she was admitted several times to the Intensive Care Unit due to heart problems. Her sentence was confirmed in December 2022.

Evelyn Pinto Centeno is a human rights defender, mother of fellow human rights defender and political activist Silvia Nadine Gutiérrez. She was 62 years old at the time of her arrest and faced trial on 9 March 2022. She was sentenced to 8 years in prison and a fine of 500 days. Of the total sentence, 3 years were for committing the crime of spreading fake news.

In a context of repression, violation of human rights, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom of association. This law, being born in this context, is a clear sign that what is intended is to instrumentalise the legal framework and criminal law to eradicate dissent.

In 2018, at 19, Samantha Jirón became involved in the civic uprising in her hometown Masaya, for which she had to flee to Costa Rica to avoid siege and persecution. In 2020 she returned to Nicaragua to be reunited with her family. She was arrested on 9 November 2021 in Managua, aged just 21, and sentenced to 8 years in prison for the same offences of conspiracy and spreading fake news.

In the trials against the WHRDs, screenshots of Facebook and Twitter postings, including retweets, were presented, together with police testimonies. Their digital activity was also investigated, and their communications were examined, even presenting instant messaging conversations with family members and acquaintances as evidence, as well as the lists of contacts found on their phones. In the case of Nidia Barbosa, Nicaraguan and Catholic Church flags found at her house at the time of her arrest were presented as evidence against her. In this way, a pattern of sentences between 8 and 11 years was repeated, combining crimes against sovereignty and the propagation of fake news.

The Mesoamerican Women Defenders Initiative (IM Defensoras) describes criminalisation as "a process that involves the use of various strategies of persecution against them, including prosecution". In the Nicaraguan chapter of the report Persecuted for Defending and Resisting, they explain that by using the legal system against women defenders, charging them and presenting them publicly in prison uniforms, they "construct an image of them as criminals in the eyes of public opinion and at the same time justify their persecution."

The four human rights defenders mentioned here were imprisoned for over a year. Those detained in Managua were first held in the cells of the Directorate of Judicial Aid or "El Chipote" and then in the "La Esperanza" Women's Prison. Nidia Barbosa, detained in Masaya, was held in the Granada Penitentiary System. All of them were held in inhuman detention conditions. According to the 2022 Report of the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights, the political prisoners "suffer cruel, inhuman, degrading treatment and torture, which have been documented and verified by their families during the few visits."

Based on these cases, families of the detainees and various human rights and feminist organisations condemned the mistreatment and violence exercised in the prisons by the National Police. The Permanent Committee for the Defence of Human Rights alleged that María Oviedo was being kept in a cell with constant artificial light, in solitary confinement and without access to medicine. The deterioration of Nidia Barbosa's health made evident the non-compliance with humanitarian provisions of the judicial system that establish that elderly people with chronic or severe health conditions should be under a regime of house arrest.

IM-Defensoras also reported the evident gender bias in the violence against women political prisoners: the questioning of their role as defenders and the distress that their work inflicts on their families, threats and sexual harassment, comments about their bodies, questioning of their sexual and emotional life, and their gender identity.

It is public knowledge that on 9 February 2023, 222 men and women political prisoners from Nicaragua were taken out of prisons and taken to the Augusto César Sandino International Airport in Managua to be illegally deported to the United States. Before the plane landed, the Nicaraguan National Assembly passed a law to reform Article 21 of the Political Constitution, stating that "traitors of the homeland" would lose Nicaraguan nationality. Among them were María, Evelyn, Nidia and Samantha, now declared stateless by the Ortega-Murillo dictatorship.

Concluding Remarks

The Special Law on Cybercrime is part of a complex legislative framework designed to provide a legal basis for censorship and persecution practices that have been implemented irregularly since 2018. Part of this strategy was approving "sister" laws such as the Foreign Agents Act, the Law on Life Imprisonment and the electoral and constitutional reforms.

The Special Cybercrime Law is far from contributing to protecting the integrity and freedoms of women using digital technologies and the internet, which would allow women survivors of violence through technology to have access to justice, together with a professional and sensitive institutional framework. On the contrary, it is a legal nonsense that is being enforced to criminalise the right to freedom of expression by considering all criticism and denunciation as "fake news"; and that can be directly applied against those who defend the right of women to live free from violence and denounce or generate data or information that does not coincide with the official government information.

Footnotes

[1] Batodano, M. (2000) Periodismo de Catacumbas. Diálogo con Manuel Espinoza y Carlos García. Memorias de la Lucha Sandinista.

[2] Redacción Central (2013, 8 de mayo) Censurados recuerdan a Guillermo Rothschuh. El Nuevo Diario.

[3] The Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation was later forced to close. Its directors and administrative staff were imprisoned, impeached, deported from the country and deprived of their Nicaraguan citizenship.

[4] Redacción Central (2021, 7 de octubre) Las absurdas pruebas de la Fiscalía en contra de la abogada María Oviedo. Nicaragua Investiga.

- 175 views

Add new comment