The spectacular developments in ChatGPT and artificial intelligence (AI) seem to dazzle us all, filling us with a mixed sense of dread and opportunity. Behind the great announcements lies a plot that is all too familiar to those of us who inhabit territories that have been colonised time and again: micro jobs with minimum wages, disregard for social rights, and the growing tendency to treat individuals as if they were machines. A feminist community-based perspective is needed to criticise and expose this model that undermines rights.

Omar (27) is a migrant living in Germany who has been a “data worker” for some years now. To describe the current workspace, Omar uses an image familiar to many: a call centre. The job opportunity came “by chance,” through a network of contacts, Omar recalls, adding how exciting the prospect of “making the internet a better place” seemed then. Now, five years later, the worst thing in Omar’s life is this job. “We are numbers to them and they completely forget there are individuals behind those numbers. We work with sensitive content here and we do not receive the treatment that is needed.”

“Data workers” are individuals who occupy positions connected with data annotation and training platforms for artificial intelligence. To better understand this kind of work profile, we consulted Matheus Viana Braz, a researcher and professor with the Department of Psychology at the University of the State of Minas Gerais (UEMG) and coordinator of the Work, Health and Subjectivation Processes Laboratory (LATRAPS), who conducts studies on the precarious work behind the artificial intelligence production chain. “These workers perform microtasks that include categorising images, classifying ads, transcribing audio and video, evaluating ads, moderating social media content, verifying information, tagging anatomical landmarks, scanning documents, and improving search engine results, among others. The best paid tasks are connected with pornographic and violent content moderation in social media,” Viana Braz notes.

In a series of emails, Omar tells me that what keeps him going is the good relationship he has with work colleagues, who have become his friends and are not necessarily technology geeks like him. He stresses that the working conditions are not what would be expected from a job based in Germany. “We are treated like call centre agents. Our salary and the fact that we only have 20 days off for vacation leave are atypical for the local setting; our working conditions in general are not comparable to those in Germany.” With respect to the sensitive content he has to assess and the impact of the data on his sensitivity, Omar says that there is a team of psychologists that offers support, “but it is hardly called on because neither I nor my co-workers find it particularly useful. I have had nightmares brought on by the self-harming content I have seen, and our team of psychologists did not really help me; instead they tried to project the company in a positive light. They told me that I was lucky to work for such a great company.”

I have had nightmares brought on by the self-harming content I have seen, and our team of psychologists did not really help me; instead they tried to project the company in a positive light. They told me that I was lucky to work for such a great company.

Milagros Miceli heads the Data, Algorithmic Systems and Ethics research group at the Weizenbaum-Institut. She also works as a researcher at the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR), where she explores ways to engage data worker communities in artificial intelligence research. We spoke with her to learn more about the working conditions of the individuals behind these promises of technological revolution. “Precarisation is maximised. The individuals employed are managed through an algorithm that is completely opaque and which cannot be appealed. When you have a boss, you can say to them, ‘This seems unfair to me,’ at the risk of being fired or losing your job, of course, but at least you have the chance and the right to object.”

Omar and his co-workers have no one they can talk to if they are removed from their job for “underperforming”; there is no one they can turn to and ask why it happened. The answer is cold and hard, given by the algorithm. Miceli emphasises that “the human aspect is lost” in a matter that is decisive for the worker’s survival.

The nature of artificial jobs

The image that emerges is that of a transparent brain supported by an android, in predominantly blue and steel shades, conveying the lightness of outer space, and the cleanliness of non-sweating robots. Omar’s reality, however, like that of many other workers who are behind these futuristic images of brilliant brains, is much more opaque.

Matheus Viana Braz invites us to look at how such images are related with the way we think about mass data production and how quickly we associate them with concepts such as deep learning, machine learning, and artificial neural networks, with big companies or technological startups, where data analysts, software engineers and other experts design data architectures capable of automating technological solutions and generating value for their shareholders. “However, we find it hard to ask ourselves where that production chain begins and where that data originates. This is a crucial issue, because in order for artificial intelligence to exist, there has to be a considerable number of people working under precarious arrangements along this production chain.”

The work cycle of moderators begins with a promise that is soon proven false. Isabella Waltz (25) began working at the age of 21 for an outsourced company that provided services for Google. “I found the job through LinkedIn. It was advertised as ‘Security and Trust Detection Agent,’ and I was intrigued because the job description said it involved a lot of research, which sounded interesting. There was nothing that I could see in the posting about moderating content. When I was interviewed I was asked if I would feel comfortable dealing with stressful content, but they said nothing about how graphic the content would be or how much time I would have to spend on that content.”

A common observation in all of these accounts is that employment conditions change as a result of excessive work loads, lack of clarity in the objectives, and the fact that there is no support from supervisors. The work involves monotonous tasks, which are sometimes assigned without asking, especially when it comes to dealing with extremely harsh images. “When we say workers are expected to act like machines because the work is repetitive,” Miceli notes, “we are not speaking metaphorically. In fact, in one of the studies we conducted, in which we analysed over 200 orders given to workers, we found that at times the instruction they were given was, ‘You have to answer such and such, think like a chatbot would.’ A reverse ‘personification’ phenomenon occurs, where machine traits are imitated when workers are asked to pass themselves off as artificial intelligence. Many instructions were along the lines of, ‘if the chat fails and a human worker has to step in, the worker is required to give binary answers.’ They are literally required to answer as if they were a machine.”

A common observation in all of these accounts is that employment conditions change as a result of excessive work loads, lack of clarity in the objectives, and the fact that there is no support from supervisors.

For the former Google content moderator, Isabella Waltz, hearing about how AI will affect jobs is a reality very far from what she experienced when she was paid USD 16 an hour, which is not nearly enough for the cost of living in Texas, United States. We know that workers in Kenya were paid less than USD 2 an hour to train the cutting-edge technology behind ChatGPT. Waltz says that while the recurring sensationalist narrative is that robots will take over human jobs, we need to highlight that “the reality is that AI and algorithms almost always depend on a poorly paid workforce to develop and perfect those technologies. Most of my friends were surprised to learn what I did at work and they were completely unaware of how widespread outsourced labour is in the tech industry.”

Focus on Latin America

While Latin America is not one of the leading regions with the largest workforce employed in this sector, there is a growing trend in that sense and it has specific characteristics, as most of the population is not proficient in English, which means there are a variety of local arrangements in place for data workers to access the industry.

The reality is that AI and algorithms almost always depend on a poorly paid workforce to develop and perfect those technologies.

Recent studies conducted by LATRAPS found, for example, that Brazil occupies a key position in the global human supply chain for intelligent technology production, through the provision of cheap, underutilised and casual labour in global microtask platforms, according to Viana Braz. The researcher explains, “In the production chain of any AI developed anywhere in the world, microwork involves extracting and generating data; it is reduced to a service and paid on a per piece/task basis, performed on digital platforms, and controlled and organised by algorithmic management. Moreover, these activities (classifying facial expressions, tagging anatomical landmarks, transcribing audio and video, moderating content, etc.) require little qualification and complexity, are poorly paid (workers earn cents, either in Dollars or in Reals, for each task they perform), and conducted informally, without any social or labour protection. We found more than 50 platforms operating in Brazil, with millions of Brazilian employees working on a regular basis.”

The result of these changes brought about by microwork, which underpins the production chain of any machine learning that is currently conducted, is, in effect, the uberisation of work. Because, to paraphrase activist and scholar Trebor Scholz, instead of helping us to share in the growth economy, it only allows us to share in the leftovers. “This means that the precarious work behind AI production is conceived as a service, paid on a per piece/task basis, at low rates (some tasks pay as little as 0.1 cents per worker), completely unregulated, and with no social or labour protection. This is perhaps one of the few markets in the world that is globally connected, with a labour force working 24/7, without any regulations,” Viana Braz notes.

Today, each context presents different concerns, depending on the country, its history and legislation. “In Argentina, the workers I have interviewed have at one point asked that they be hired as employees, so they would no longer be freelance. And they were. But we are talking about a specific company, not all companies,” Miceli says. The researcher points out that in countries such as Bulgaria, workers fought to remain independent and not have officially registered contracts.

In order to understand this issue intersectionally, we need to have more information. While research in Brazil does not yet allow us to establish the impact of race markers, there are important indicators of the effects of geographical, class, gender, and educational level markers. “Our study suggests that the gender disparities that cut across the labour market are reproduced [in that sector] as well. Women who work in platforms appear to have more dependants (especially children) than men, in addition to working more hours per day than men on those platforms.”

We came across a case in which a woman performed these tasks at night while she breastfed her newborn child.

Viana Braz notes that mothers, in particular, work more hours and more regularly on platforms, but for shorter periods at a time, “which may indicate they are now spending their leisure or rest time working on microtask platforms. In our study, for example, we came across a case in which a woman performed these tasks at night while she breastfed her newborn child. Microwork, therefore, represents a third work shift for these women, whose time is now even more fragmented."

Artisanal resistance tactics

Repetitive tasks, working with sensitive images, constant monitoring, and performance assessment based on opaque metrics. Omar says that it is not uncommon for content to be left pending if the worker who was dealing with it felt overwhelmed and had to take a break or even the day off, so that when you are faced with such content, “you feel more and more drained as an individual because you will see the same content that someone else set aside.” For her part, Isabella Waltz says she had a problem with one of her bosses, “He did not train new employees properly, so I had to put in a lot of extra work with them to keep up the quality of the team. That was very stressful, as Google could terminate our contract at any time if the quality of our work declined. He also treated the women in the office badly, especially the women of colour. Two of our new employees, who are Latina women, told me that he reacted aggressively when they approached him with questions about things for which they had not been properly trained.”

Despite how harsh these jobs are, the researchers consulted say that there are solidarity tactics that have emerged among the mass of workers, in particular those who work remotely. “In Venezuela, workers organise a lot on internet forums, such as Facebook groups or Telegram groups. And resistance is done through micro actions, which may be small but serve to change the workers’ perspective. For example, they help each other understand certain tasks when work becomes difficult because most tasks are in English, and these groups of workers are not made up of native English speakers. So they first need to understand what the client is asking for, identify clients who do not pay, or who pay too little.”

So far there are no successful attempts at unionisation in this market anywhere in the world, although workers are standing up for themselves through different cooperatives and new forms of organisation that challenge the uberisation of the world. In this sense, the first major collective mobilisation experience in the AI data training market was furthered by Lilian Irani and Six Silberman in early 2010. That experience led to the construction of Turkopticon, a community that sought to rebalance the power and information asymmetry that existed in Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT). Turkopticon functions as a plug-in connected to AMT, where workers share and rate task requesters according to generosity, communicability, fairness and reactivity criteria. This helps avoid negative evaluations and makes it easier to search for employers that offer fairer prices and more favourable tasks. The system also has its own forum and the possibility of issuing reports.

As long as these technologies are designed by white cis men from Silicon Valley who make five times as much as we do, we will continue to be in trouble.

Finally, Miceli argues that a feminist perspective of the crisis we are experiencing with the emergence of the promises of “all-powerful machines” needs to be bold enough to say “this does not work for us, these technologies are not designed with me in mind, with my communities in mind.” So she invites us to think about what kind of technologies would be good for us and for our communities. “These are not rhetorical questions but important calls to action, because as long as these technologies are designed by white cis men from Silicon Valley who make five times as much as we do, we will continue to be in trouble.”

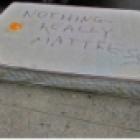

In this desert of silver androids with blue backdrops and women workers who brutally expose themselves, body and soul, it is vital that we keep denouncing big tech’s abuse. We need to take up that meme that began circulating a few days ago, which shows a hand-stitched message that reads: “Long live artisanal intelligence.” We need to become stronger in the face of the destruction wreaked by the growing precarisation, move past outrage and join forces in a communal, collective and cyber-feminist way, to expand our imaginations and see how we can build care, enjoyment and struggle strategies as technologies, so as not to be blinded by the attempt to erase the individuals breathing behind the algorithms.

- 344 views

Add new comment