Illustration by Fernanda Serejo for FIRN

The research report “Feminist digital forensics: A study and a proposal for development” is the unfolding of our incursion into the field of digital forensics and its applications for civil society, particularly in cases of technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV).

Digital forensics is a technical field deeply connected to the criminal justice system, where forensic experts and other actors, such as lawyers and police officers, work together in legal investigations. It became especially relevant for us at MariaLab when we faced the challenges of creating a feminist helpline to address digital security emergencies – Maria d’Ajuda.[1] Multidisciplinary expertise is essential in supporting gender-based violence cases. A single case may require knowledge of digital security, physical security, psychosocial support, legal matters and more. In an incident response context, digital forensics could provide critical insights – clarifying what occurred, how it happened and even generate evidences for legal reparation. At the very least, it can enable helplines to identify complex incidents and seek other organisations for detailed forensic analysis – referencing cases in a targeted and informed manner.

There is a growing interest of civil society in digital forensics amid escalating digital threats to human rights defenders, particularly through surveillance tools on electronic devices. Pegasus Spyware[2] is perhaps the most well-known example. Yet it represents only one facet of a more complex problem.

Pegasus is a spyware developed by the Israeli company NSO Group,[3] notorious for targeting journalists and activists globally and operating silently. It can be covertly installed on mobile phones using a zero-click exploit technique, infecting devices without any user interaction. Pegasus can access various data and functions on infected devices, including contacts, messages, photos, microphone, camera and location – violating individuals' rights to privacy.[4]

Since 2016 organisations like Amnesty Tech[5] and Citizen Lab[6] have published relevant forensic reports[7] on governmental spyware, stirring the topic among civil society. In July 2021 the Pegasus Project[8] – a collaborative investigation by 17 international media organisations – revealed a list of over 50,000 phone numbers potentially targeted for surveillance by NSO Group’s powerful malware.

There is a growing interest of civil society in digital forensics amid escalating digital threats to human rights defenders, particularly through surveillance tools on electronic devices.

To the practices of digital forensics for human rights (also known as consensual digital forensics), these findings posed a paradigm shift. For the first time there was a large-scale analysis of hundreds of likely targeted devices, featuring activists, journalists and human rights advocates.[9] The Pegasus Project highlighted how most attacks remain invisible to victims, emphasising the need for systematic investigations. At same time, it provoked a strong backlash from human rights defenders, who grew increasingly concerned about potential surveillance of their work.

This climate of uncertainty sparked a surge in demand for support for Digital Security Helpdesks for Civil Society (DSHCS). Even long-established, rapid-response organisations found themselves inundated with an unprecedented volume of requests, overwhelming their capacity.

The growing impact of spyware and the need for advanced expertise have driven efforts to strengthen forensic capabilities within the DSHCS community. In Latin America, collaboration with Global North reference organisations has been common when investigating suspected malware cases. While these partnerships enhanced forensic credibility and advocacy evidence, they have also created dependencies on more technically advanced partners.

The challenge is twofold. On one hand, there is a shortage of professionals with technical expertise and procedural knowledge required in digital forensics. On the other hand, there is a lack of individuals who possess the techno-political perspective necessary to properly address and comprehend the unique requirements of human rights work.

Distinct from traditional criminalistics – which focuses on state-led prosecution – the civil society approach for digital forensics is characterised by its independent methodology, designed to protect activists, journalists and vulnerable groups who are routinely subjected to illegal surveillance. This approach is called consensual forensics, and it has several distinctive characteristics:

| Traditional forensics | Consensual forensics | |

| Actors involved | Key institutional actors including law enforcement agencies, the judiciary, military institutions, private sector entities and academic institutions. |

Civil society groups such as DSHCS, human rights defenders, activists, digital rights advocates, academia, lawyers and the broader human rights field. |

| Possible applications |

|

|

| Methodologies |

|

Unlike corporate or legal forensics, forensic analysis for human rights defenders (HRD) requires fully informed consent. The affected person consents to the investigation and must understand each step – what data will be collected, how it will be used, possible outcomes and limitations – before authorising the process. Thus, the affected person is centred as the protagonist, ensuring that they understand the process, even if they lack specialised technical knowledge, and they maintain control over the next steps after the results of the investigation.[12]

|

| Forensic Tools |

A vast array of tools,[13] including open-source and enterprise-level solutions. Both types are widely used by forensic analysts worldwide, however Latin America’s law enforcement agencies rely heavily on commercial tools with user-friendly interfaces, such as Cellebrite, Verint and Magnet forensics.

|

Apart from open-source forensic tools, some developers have taken the initiative to create custom tools that integrate existing open-source components with newly developed functions specifically tailored for civil society. Most notable examples are MVT,[14] AndroiQF,[15] PiRogue and Colander.[16]

|

| Acquisition |

Always performed in-person in accordance with each country’s chain of custody and international best practices.

|

Preferably organisations work with local partners who handle the first triage and collect forensic data in-person, but in most cases they are forced to conduct extractions remotely.

|

Despite the developments around digital forensics being driven by the spyware crisis, forensic analysis itself can be highly relevant to the investigation of other types of digital threats, particularly those commonly reported by helplines supporting TFGBV cases.

The predator in your pocket

Amid the countless scandals and billions generated by the spyware industry, a parallel market is rapidly developing. Classified as stalkerware, this software category has surveillance capabilities but is routinely marketed to the public to facilitate intimate partner violence (IPV), abuse, or harassment. While some companies claim legitimate uses like parent-child monitoring or employee control – though still problematic – these tools are commonly repurposed for TFGBV. Citizen Lab's 2019 study exposed companies actively promoting their software for stalking purposes, enabling abusers' obsessive behaviour that violates privacy and threatens victims' safety.[17]

While some companies claim legitimate uses like parent-child monitoring or employee control – though still problematic – these tools are commonly repurposed for TFGBV.

TFGBV is characterised by specific distinguishing factors: perpetrator anonymity, low technical barriers to committing offences and permanent record of violating content on the internet. While abusers hide behind anonymity, victims face ongoing re-victimisation as online content proves nearly impossible to fully erase.[18]

This violence thrives by exploiting vulnerabilities in legitimate app functions. So-called dual-use apps – which serve both proper and malicious purposes – often come pre-installed on devices. Poor configuration of features like Find My Phone or parental control apps creates loopholes for attackers to easily access and monitor data. The digital gender gap is a huge component of these risks, as victims frequently delegate account and device security to partners who exploit this dependence for control and stalking.[19] This pattern appears consistently across TFGBV support groups, revealing stalkerware as less prevalent than dual-use software abuse.

Much of TFGBV assistance is provided by feminist organisations and collectives that are part of DSHCS and are deeply committed to addressing gender-based violence in all spheres. In recent years, many of these groups structured their work in the form of digital security helplines, specially In Latin America.[20] Despite originating from diverse contexts and organisations, they share a common political perspective that prioritises survivors' needs, collectivity, autonomy and intersectionality as fundamental elements for creating protection strategies that go beyond technical solutions. These security measures respond to a combination of subjectivity, co-responsibilities and mutual care.[21]

Digital security helplines are not new to the community of DSHCS, with several known examples such as Access Now, Frontline Defenders and many others.[22]. Most of these helplines, however, focus their support on human rights defenders and civil society organisations, not covering situations outside these groups. When a new case arrives, these helplines typically run a triage process to identify, among other things, if the person seeking help is an activist or is working under a civil society organisational structure. However, when examining the human rights landscape through a broader lens, it becomes evident that digital violations against socially marginalised groups also pose a significant human rights concern, even when the affected person does not belong to formally organised civil society structures. This is why the feminist helplines – as part of the broader community of DSHCS – play a fundamental role in providing direct assistance to victims of gender-based violence, racism and LGBTQIA+ phobia.

The feminist digital helplines interviewed in this study are relatively new, having been established within the last decade – some during the COVID-19 pandemic.[23] Beyond the health and economic crisis, recent scholarly literature converges on the notion that the confinement, isolation and heightened tensions engendered by the pandemic exacerbated the prevalence of violence against women and gender-dissident individuals while hindering their ability to seek assistance. Simultaneously, the widespread migration of labour, academic and social activities to online platforms, intensified during the pandemic and led to a significant increase in time spent online. In response, the utilisation of online support networks became highly prevalent.

The challenges in the daily work of feminist digital helplines are remarkably similar when faced with the need to handle cases requiring specialised knowledge of digital threats. While very experienced in providing first aid to the supported persons, these groups’ capacity for technical examinations is frequently limited by quick check-up constraints. Additionally, online support and the limitations of remote communication pose significant challenges for devices’ data collection. This is deeply alarming, particularly given that feminist helplines log a high volume of incidents of suspected surveillance, where the victim fears there is illegal spying software on their phone. These cases often end without a resolution.

Given this problem, we questioned how digital forensics can serve as a tool against TFGBV.

The development of feminist helplines through the systematisation and improvement of consensual digital forensics is our main objective. We started from the hypothesis that improving knowledge for identification and collection of evidence for forensic analysis would improve our collective capacity to respond and generate data about digital threats.

Our footsteps towards feminist digital forensics

For the development of the study, we dialogued with two types of interlocutors: international organisations that respond to civil society security incidents, recognised as references in this field; and with feminist digital security helplines from Latin America, with whom we have already collaborated on prior projects and established a relationship of trust. The entire research process unfolded through constant interaction with our interlocutors divided into multiple activities:

- Seven interviews with representatives from expert organisations, references in digital security support to civil society and human rights defenders

- Online questionnaire with the five feminist digital helplines participating in the study, with the goal of mapping initial challenges and common characteristics

- Participation in the consortium of Latin American organisations led by Fundación Acceso;[24] it provided an opportunity to learn and gather information on the tools, methodologies, protocols and practices currently used to analyse and respond to advanced digital threats. We attended three in-person meetings from March to July 2024.

- Contributing as trainers in a digital security capacity-building meeting led by FrontLine Defenders[25] and the Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders (IM-Defensoras)[26] (July 2024) aimed at feminist organisations and activists in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the preparatory meetings for this gathering, we had the opportunity to discuss support methodologies and protocols with other feminist digital security educators, and from there we developed the idea of the feminist support chain.

- Organisation of an immersive in-person meeting with members from the five feminist helplines participating in this project

The table below presents the research partners we worked with:

| Organisation |

Key contribution for digital forensics |

| SocialTIC https://socialtic.org |

SocialTIC is a Mexican organisation founded in 2012 that empowers activists, journalists and human rights defenders through secure digital technology, open data and infoactivism. In 2016, it co-led the #GobiernoEspía[27] project with CitizenLab, Artículo 19, and R3D, exposing NSO Group’s Pegasus malware targeting journalists and activists in Mexico – later expanding forensic analysis of spyware across Latin America. In 2025, SocialTIC launched SocialTIC Forensics,[28] a repository promoting ethical digital forensics as a human rights tool.

|

| Conexo https://conexo.org |

Conexo is a Venezuelan digital security organisation that supports civil society and human rights defenders through a holistic approach. Its services include independent security audits, holistic security training, organisational security, policy development and advanced technical services – such as malware analysis, phishing investigations and malicious infrastructure monitoring. Conexo co-developed Infuse,[29] a community-driven framework to advance technical expertise among digital security professionals.

|

|

Access Now |

Access Now is a global non-profit, founded in the U.S. in 2009, dedicated to defending digital civil rights. Its work spans many branches like advocacy and public policy, campaigns and mobilisation, as well as grant funding and research, but it’s better known for it’s helpline for emergency support to journalists and rights defenders.

|

|

Fembloc |

Fembloc is a Catalonia-based helpline founded in 2021 specialising in addressing digital gender-based violence, offering support to victims – primarily women and LGBTQIA+ individuals. The organisation provides psychological support, technical support and legal counsel. Additionally, Fembloc has developed forensic expertise to enhance its helpline services and provide digital forensic analysis for legal proceedings.

|

| Defensive Lab Agency https://defensive-lab.agency/ |

Defensive Lab Agency is a Europe-based organisation focused on developing open-source digital forensic tools through its PTS-Project.[30] Its most known tools are Colander, a self-hosted incident management platform, and PiRogue, an open-source hardware solution built on Raspberry Pi for real-time traffic analyses. Beyond creating affordable investigative tools for civil society, the organisation also provides training, security audits, penetration testing and digital forensic analysis to support legal and investigative processes.

|

| Frontline Defenders https://frontlinedefenders.org/ |

Founded in 2001 as a small rapid-response initiative, Frontline Defenders has grown into a global team of 80+ professionals supporting at-risk human rights defenders through holistic, case-by-case protection. The organisation provides protection grants for emergency funding; capacity building trainings in digital security, safety, and well-being; training of trainers to develop local digital protection mentors; and maintains an emergency helpline for crisis response and proactive risk monitoring.

|

| Amnesty International Security Lab https://www.amnesty.org/en/tech/ |

The Security Lab is Amnesty Tech – part of Amnesty International's technology and human rights division established in 2016-2017. This multidisciplinary team investigates cyberattacks against activists and human rights defenders and develops tools like MVT (Mobile Verification Toolkit)[31] and AndroidQF.[32] Their work encompasses three key areas: technical research; collaboration with digital rights communities; and capacity-building through initiatives like the Digital Forensic Fellowship, which trains civil society in advanced forensic techniques.

|

| Navegando Libres por la Red https://navegandolibres.org/ |

Born from Taller Comunicación Mujer, this feminist helpline emerged in 2016 after monitoring gender-based violence and abortion cases in Ecuador. With specialised training in feminist digital approaches, the initiative serves women, children, adolescents, LGBTQIA+ individuals (including migrants/refugees), and feminist/human rights groups. Their work focuses on holistic digital protection training and tailored strategies to counter gender-based digital violence, applying feminist principles to internet safety and technology use.

|

| Centro S.O.S. Digital https://sosdigital.internetbolivia.org/ |

Born from Internet Bolivia in 2019, S.O.S. Digital emerged as a feminist, intersectional helpline to fill critical gaps in supporting digital violence. The initiative provides emotional, technological and legal assistance to adolescent girls, women, survivors, activists, LGBTQIA+ individuals, journalists and women in politics – offering a vital safety net against technology-facilitated abuse.

|

| Luchadoras https://luchadoras.mx/ |

Emerging from groundbreaking research on digital violence against women and gender-diverse individuals in Mexico, Luchadoras began as a study that evolved into vital support services. Their initial mapping of digital violence organically grew into case support, which soon became an institutional priority. The organisation provides legal counsel, psychological support and technical support for digital platforms and self-care, primarily for women, youth and gender nonconforming individuals facing online abuse.

|

|

Línea de atención de Técnicas Rudas |

Técnicas Rudas, a Mexico-based organisation, has worked with digital security since its creation, providing case support since 2017. They formally launched a helpline in 2021 through an Access Now partnership – expanding their services to include free emergency response. Their approach centres on risk analysis-driven follow-ups, digital security protection plans and holistic support for LGBTQIA+ communities, land defenders, journalists and human rights defenders facing digital threats.

|

|

Maria d’Ajuda

|

Brazil’s MariaLab had long addressed digital security incidents through informal channels, but the surge in gender-based violence during COVID-19 prompted the 2021 launch of Maria d’Ajuda – a dedicated helpline. The initiative provides digital care training, organisational security, and social media protection, primarily for women, LGBTQIA+ communities, feminist groups and human rights activists facing technology-facilitated threats.

|

It is important to highlight that in this research we occupy a dual role as both researchers and participants interested in the investigated theme. This duality between “investigating” and “participating” is natural to our practice as a feminist hacker organisation, and when applied in a scientific research context, it requires additional caution and reflection. We understand that our personal experience and political engagement with the researched topic are integral parts of the investigation process and that critical reflection on our own positions is fundamental for knowledge production. This also includes recognising the position of "power and privilege that come with 'community trust' due to shared identities".[33]

This non-objectivity also came with a responsibility to ensure that the ideas, data and experiences gathered in our research does not merely reflect the perspectives of those writing it. Action research – an investigative process that intentionally seeks to create practical effects in the reality being studied – was our chosen approach.[34]

However, this is just one of several ethical and technopolitical considerations, with other key points and ideas discussed in these interviews. Here we will introduce three key points, illustrated by inspiring words from these conversations: the role of psychosocial views in digital forensic work, community work as a source of strength and intersectionality in digital care.

[B]ecause there's been a lot of media attention and public attention on spyware, a lot of people come to us because they think it's highly likely that they might have been targeted. And so there's a lot more interest now than there was, as we said. And so when you're working with the feminist helplines, I think this type of triaging process is really important because it's really scary. People are very worried about spyware, but it's often not the main threat that people are facing.[35]

Forensic analysis alone cannot fully address the complex threat models behind surveillance, gender-based violence or the persecution of activist work.

We advocate for an approach that recognises the technical and political as inseparable dimensions in both the development of and lived experience with technologies. When applied to feminist helplines practices, this perspective reveals its transformative potential: technical excellence in forensic analysis is not only compatible with psychosocial care, but is strengthened when combined with it. In operational practice, this translates into methodologies that integrate investigative rigour with socio-political commitment, where detailed examination of digital evidence goes hand in hand with attention to the emotional and social impacts experienced by affected people. This breaks with the false dichotomy that opposes technical objectivity to the subjectivity of care, proposing instead a comprehensive model of action that recognises the complexity of TFGBV and of digital threats in general.

While care is undoubtedly exercised during incident response, formal psychosocial protocols rarely receive the same emphasis as in gender-based violence cases, where they constitute a primary response. This imbalance prompts crucial questions about the psychosocial consequences of spyware surveillance.[36] However, it’s worth noting the risk of an essentialist perspective[37] that frames gender-based violence (frequently narrowed to mean violence against women) as primarily emotional or abstract, thereby neglecting its material realities.

Our aim is to help human rights defenders at risk who are working in their countries [...] And for this, we have, as I said, network of trust, and we have people based in the regions who are specialised in understanding the circles, the society and the needs of human rights defenders, and building the network of information and trust.[38]

Forensic analysis alone cannot fully address the complex threat models behind surveillance, gender-based violence or the persecution of activist work. Digital forensic training of facilitators who are closer to the victims is also relevant to this chain and can contribute to more effective responses. This community itself consists of diverse individuals, each bringing their own experiences, activism, cultures and passions. When these elements intertwine, they create a rich tapestry of knowledge that manifests best in broader discussions rather than narrowly ultra-specialised activities.

So, our communication methods keep adapting based on digital gaps, the tools people already use, and the paths they’ve taken to reach us – because these factors change constantly. All of this also influences which communication channels we prioritise.[39]

We – as part of feminist helplines – come from the understanding that human rights violations – particularly gender-based violence, racism, ableism and xenophobia – are socially structured and affect individuals not only because of their activism but because of their identities. While these groups may not be the primary targets of high-cost surveillance software, they are still impacted by a culture of digital surveillance and control that predates and extends beyond the spyware crisis.

Common ideas and challenges, chained togetherDuring the various phases of working with the feminist helplines, we identified several common ideas, as well as a number of key challenges.

A foundational and common concept in feminist helplines' care approach is the ongoing support that is offered – also called acompañamiento in Spanish or acompanhamento in Portuguese. This terminology represents an ongoing collaborative process rather than a one-time service provision. Rooted in feminist principles, this approach emphasises autonomy and capacity-building for those seeking support, focusing on a learning process based on three interconnected goals:

- Building capacity through knowledge by providing information and facilitating discussions on how technology and the internet work and what political issues are involved.

- Developing practical skills to independent comprehension and informed decision making about safety measures.

- Introducing secure and free alternative tools to expand communication options beyond reliance on large commercial platforms (Big Tech).

The principle of fostering autonomy present here also relates to the self-determination of the supported person. Above all, safety measures must align with and respect the individual's choices and preferences. This understanding is rooted in the longstanding practice of feminist movements in supporting victims of sexual violence. Even in technical cases, there is no single correct answer. For this reason, the initial hearing and risk assessment are essential for fully understanding each case.

One of the most relevant aspects of this comparison analysis was the identification of key challenges in case management. Common issues include the difficulty of holding social media platforms accountable for adequately moderating violent content, frequent disruptions in support services due to unreliable internet access and the overlap of multiple forms of violence in online abuse cases. However, the most critical finding is that all helplines reported a need for strengthening technical capacities to effectively address cases involving digital surveillance and illegal monitoring.

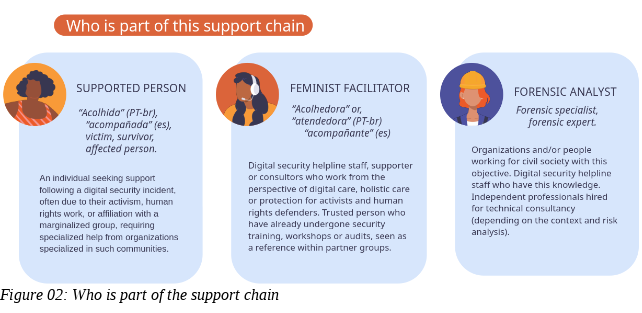

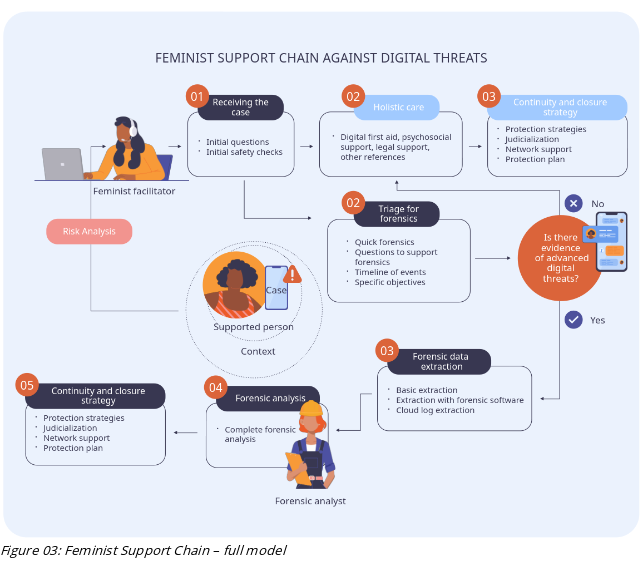

To answer to this need we designed a visual summary of our mutual support process and added a proposal for integration with consensual forensics, to which we called Feminist Support Chain. The details of this proposal have been compiled in an informational guide, which extended our research to a more practical document.[40] This supplementary resource includes case examples, provocative questions and testing models. These technical steps are supported by several linked procedures that we either wrote or curated, whose language is tailored to the field of digital care – particularly in the new phases of triage for forensics and forensic data extraction.

The Feminist Support Chain

The first step toward developing this model was the realisation that, despite each helpline's unique characteristics, our field shares a common approach to responding to digital incidents.

Initially this design contained no digital forensic practices or specialised triage. All investigation and triage activities conducted by the helplines were concentrated in the moment for receiving the case and doing individualised check-ups, later referred to specialised support.

To this model, we added a proposal for integration with consensual forensic analysis. Our expectation was to expand this support chain model by including partner organisations that accept referred cases, with whom the feminist facilitator would interact directly. In this proposal there is a new key actant called the forensic specialist and two additional phases that the feminist facilitator can perform before the analysis: triage for forensics and forensic data extraction.

By incorporating forensic triage and forensic data collection phases into feminist helpline operations, we hope to facilitate the same type of qualified relationship that already exists between these organisations. Obviously, nothing prevents forensic analysis from being conducted internally by helplines that wish to build this capacity (as is the case with FemBloc and Maria D'ajuda), but when looking at the support chain as a whole, we recognise that diversity is necessary since no technical practice answers all questions.

The inclusion of the triage for forensic phase in the Feminist Support Chain represents a new layer of analysis, aiming to identify evidence of more sophisticated digital threats. Unlike the initial triage – which focuses on more common causes like misconfigured dual-use applications or unauthorised access to cloud accounts – at this stage we look for patterns of suspicious activity. This analysis does not require specialised forensic software and can be done through reviewing system settings and key indicators via the device's graphical interface. The goal is to detect suspicious apps or configurations that may indicate stalkerware or other malware, while assessing whether a forensic analysis is necessary.

From a holistic perspective, this qualified evidence-gathering also functions as a psychosocial tool: the technical review process, when conducted during support with transparency and empathy, helps validate concerns and reduce the emotional impact of digital violence.

Once there is any indication of the need for forensic analysis, the feminist facilitator assumes the crucial role of informing the victim and conducting the data extraction. This phase is conditioned by multiple factors: the professional's technical expertise, the supported person's conscious choices, operational limitations (such as the need for remote collection and internet quality), and the potential judicial use of evidence – in which case forensic protocols must be strictly applied, including preserving the chain of custody.

Regardless of these factors, there are various extraction possibilities that are not limited to a single technical approach. The feminist facilitator can collect relevant contextual information, such as specific analysis objectives and reconstruction of an incident timeline with date and time records. Some evidence can be obtained without specialised tools, like system logs and cloud account access logs. Even when forensic software is necessary, there are options with simplified interfaces, like AndroidQF, which can be used by mostly anyone after proper training.

One practice in particular stood out in our trajectory: extracting Google account data using Google Takeout.[41] Since Google accounts are intrinsically linked to Android devices through app synchronisation, login credentials and system resource access, the analysis of this data can be complementary and possibly reveal unauthorised access to files, emails, security settings and other sensitive information in the Google ecosystem.

Two aspects of this technique deserve emphasis: first, this information is highly relevant for TFGBV cases commonly handled by feminist helplines, such as account theft and unauthorised access to personal files. Second, we identified a significant gap where there are few references about the forensic usage of this data, both in traditional forensics and consensual digital forensics. This void in literature and existing practices motivated us to change our plans and write a full tutorial, which we believe is a new resource that will be valuable for this field.[42]

10 principles for feminist digital forensics

By recognising the complexity of violence experiences, the process of acompanhamento conducted by helplines provide safe spaces for affected individuals to voice fears, insecurities and doubts. Active, empathetic listening forms a fundamental pillar of this process, fostering trust-building relationships.

Given the uniqueness of this work, we conclude this study by expanding our initial research question. Beyond examining how digital forensics could support the fight against TFGBV, we also find that the feminist perspective of care makes a significant contribution to the development of consensual digital forensics.

This begins with re-examining a few key concepts:

We conclude that feminist digital forensics can only exist within a feminist support cycle. This cycle begins at the first point of contact, and it extends far beyond evidence collection or legal case-building, actively pursuing pathways to holistic repair. We recognise that the search for judicial justice must not overshadow other forms of reparation, such as restoring mental well-being and reclaiming autonomy.

This approach is necessary because, historically, women, gender-dissidents and racialised groups have been systematically rendered invisible in the production of technological knowledge – a domain culturally constructed as masculine. This erasure produces a paradox: one that embodied minorities navigate daily, yet under the weight of systemic fear.

Our shared goal as helpline practitioners – and above all, as digital rights activists – is to transform digital technology and the internet into liveable spaces: spaces where people can chart their own paths, and where technology itself can be reimagined through the prism of our identities and struggles.

Footnotes

[2]Pegg, D., & Cutler, S. (2021, 18 July). What is Pegasus spyware and how does it hack phones? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jul/18/what-is-pegasus-spyware-and-how-does-it-hack-phones

[4]Cardillo, M., Fischer, S., & Kekre, A. (2023, 7 July). Targeting, infecting, surveilling, harming. Geneva Graduate Institute. https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/sites/internet/files/2024-01/ARP%20FINAL%20REPORT%20-%20Aditi%20Amol%20Kekre.pdf

[7]Scott-Railton, J., Marczak, B., Guarnieri, C., & Crete-Nishihata, M. (2017, 11 February). Bitter Sweet Supporters of Mexico’s Soda Tax Targeted With NSO Exploit Links. The Citizen Lab. https://citizenlab.ca/2017/02/bittersweet-nso-mexico-spyware/

[8] Pegg, D., & Cutler, S. (2021, 18 July). Op.cit.

[9] Forbidden Stories. (2021, 18 July). About the Pegasus Project. Forbidden Stories. https://forbiddenstories.org/about-the-pegasus-project/

[10] Although it does not focus on this area, the SAFETAG methodology has specific activities on digital forensics. https://safetag.org/activities/forensic_analysis/

[11]International Organization for Standardization. (2012). ISO/IEC 27037:2012 Information technology — Security techniques — Guidelines for identification, collection, acquisition and preservation of digital evidence. International Organization for Standardization. https://www.iso.org/standard/44381.html

[12]SocialTIC. (2025). Explainer: Introducción a la forense digital consentida para la defensa de los Derechos Humanos. https://forensics.socialtic.org/explainers/01-explainer-introduccion-forense-digital/01-explainer-introduccion-forense-digital.html

[17]Parsons, C., Molnar, A., Dalek, J., Knockel, J., Kenyon, M., Haselton, B., Khoon, C., & Deibert, R. (2019). The predator in your pocket: a multidisciplinary assessment of the stalkerware application industry. CitzenLab. https://citizenlab.ca/2019/06/the-predator-in-your-pocket-a-multidisciplinary-assessment-of-the-stalkerware-application-industry; Mason, C., & Magnet, D. (2012). Surveillance studies and violence against women. Surveillance & society, 10(2), 105-118. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v10i2.4094

[18]Taller Comunicación Mujer. (2023). Mediciones de la violencia de género digital en América Latina y el Caribe. https://navegandolibres.org/mediciones-de-la-violencia-de-genero-digital-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-aborda-las-metodologias-y-contenidos-generados-sobre-la-tematica-ademas-de-los-retos-en-su-abordaje/

[19]Ibid.; Havron, S., Freed, D., Chatterjee, R., McCoy, M., Dell, N., & Ristenpart, T. (2019). Clinical Computer Security for Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity19/presentation/havron

[21]Araujo, D., Manica, D., & Kanashiro, M. (2020). Tecnopolíticas de Gênero. Cadernos Pagu, 59. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?cript=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-33202000020…https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449202000590000; Natansohn, G., & Reis, J. (2020). Digitalizando o cuidado: mulheres e novas codificações para a ética hacker. Cadernos Pagu, 59. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449202000590005

[23]Among the five lines that are part of this study, only Navegando Libers and S.O.S. Digital were launched before 2020, in 2018 and 2019 respectively. The others began their development during the COVID-19 pandemic, mostly motivated by an increase in the number of cases.

[33]Hussen, T. S. (2019, 29 August). “All that you walk on to get there”: How to centre feminist ways of knowing. GenderIT. https://firn.genderit.org/blog/all-you-walk-get-there-how-centre-feminist-ways-knowing

[34]Tripp, D. (2005). Pesquisa-ação: uma introdução metodológica. Educação e pesquisa, 31(3), 443–466. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-97022005000300009

[35]Interview with Amnesty Tech, 17 October 2024.

[36]These issues will not be explored within the scope of this study, although existing research has already begun this analysis. Fundación Acceso has done an excellent research about the psychological impacts of spyware. https://pasalavoz.acceso.or.cr/Estudio_de_impactos/

[37] Heyman, G. D., & Giles, J. W. (2006). Gender and Psychological Essentialism. Enfance, 58(3), 293-310. https://shs.cairn.info/revue-enfance1-2006-3-page-293?lang=fr

[38]Interview with Frontline Defenders, 1 October 2024.

[39]Interview with FemBloc, 1 October 2024.

[41] This tool was developed by Google to enable users to download their stored data. Some of the extracted information contains forensically relevant data for Android device investigations: https://takeout.google.com

- 72 views

Add new comment