Illustration by Desmond Asak (Renurm)

Abstract

This research was conducted at four higher education institutions in South Africa: the Independent Institute of Education, the University of the Witwatersrand, North-West University, and the University of KwaZulu-Natal. The study employed a mixed methods design to generate evidence-based data to analyse participants’ understanding and experiences regarding technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV) on social media and online dating platforms. Data was collected through surveys and focus group discussions to examine how South African youth navigate digital spaces and the associated risks involved in building intimate relationships and forming identities.

The quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that most participants are unfamiliar with the term technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV), even though many have witnessed or experienced technology-related abuse and its emotional effects. This lack of conceptualisation of the phenomenon limits victims from reporting their experiences as a crime. In addition, there is limited societal awareness and normalisation of TFGBV as an online harmless experience compared to physical violence or abuse. These factors contribute to the under-reporting of TFGBV cases among youth. The research also identifies vulnerabilities among marginalised groups such as LGBTQI+ individuals, Black women affected by racial fetishism, and single mothers.

TFGBV in South Africa

Globally, youth increasingly turn to digital platforms for connection. In South Africa, this phenomenon was apparent on platforms like MXit (now defunct),[1] and more recently Facebook[2] and WhatsApp[3] as dominant channels for youth communication and interactions. However, social media’s evolution from networking to relationship-building has normalised digital intimacy[4] while obscuring risks exacerbated by anonymity, deception and increasing vulnerabilities for abuse due to heightened trust and emotional investments.[5]

In South Africa, TFGBV intersects with systemic gender inequality,[6] with approximately 33% of women reporting experiences of online harassment.[7] In the South African context, more needs to be done to understand the occurrences of TFGBV, as most literature focuses on offline GBV[8], despite the country’s expansive digital engagement among its youth population.[9] Currently, gender-based violence (GBV) is more broadly researched mainly because it is deeply entrenched in the South African society and higher education institutions, reflecting its high prevalence rates despite the significant under-reporting due to fear, stigma and distrust in institutional processes.[10] However, with an increased number of South Africans between the ages of 18 to 34 years old being active users of social media spaces[11] and of university students using online dating platforms such as Tinder,[12] these spaces have been identified with the possibility of amplifying risks of exploitation and violence with serious psychological implications.[13] The emergence of digital technology for social interactions and connections has added new dimensions to GBV, transforming traditional forms of harassment and abuse into more pervasive and less easily regulated online forms.[14]

Over the years, several South African universities have documented rising TFGBV cases linked to dating, the growing adoption of social media apps and its possible association with TFGBV.[15] The rise of online dating apps such as such Tinder, Bumble and OKCupid[16] as well as social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram[17] has fundamentally altered how students form and maintain intimate relationships[18] as well as create environments where anonymity, accessibility and virality facilitate various forms of TFGBV.[19] However, the fear and stigma associated with reporting TFGBV may have contributed to its under-reporting and the persistence of a culture of silence.[20]

Project objectives

This study was designed to achieve the following objectives:

- To identify the factors that shape the perception of South African university youth’s usage of social media and online dating apps in relation to TFGBV.

- To classify the types and frequencies of TFGBV experienced by South African university youths when using social media and online dating apps.

- To examine how TFGBV intersects with diverse groups in South Africa.

- To understand the emotional impacts of TFGBV on South African university youths.

- To explore the reactions and responses of South African youths to TFGBV. experiences

Research methodology

Purposive and snowball sampling methods were used to reach a broad range of students for an online survey. Participants had to be over 18 years and enrolled in one of the selected campuses. Probability sampling was not feasible due to the logistical challenges and privacy restrictions imposed by the South African Protection of Personal Information Act 4 (POPI Act).[21] After a thorough cleaning process of the data – which involved removing incomplete, duplicate, and invalid responses – 620 responses out of 721 were deemed complete and valid for statistical analysis.

Participants for the focus group discussions (FGDs) were selected through purposive sampling to ensure diversity in gender, age, academic level and experiences, adhering to ethical and institutional requirements. Data was recorded on phones and laptops and transcribed using Sonix.ai. In the analysis, aspects of participants’ sexuality are only mentioned if, in their responses, they publicly make their identities known. Research assistants noted racial and gender differences, and these were included in the qualitative analysis.

Discussion of research findings

Intimate partner-seeking behaviour on social media and online dating platforms

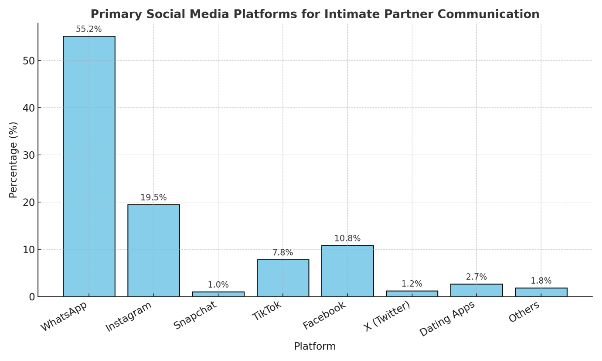

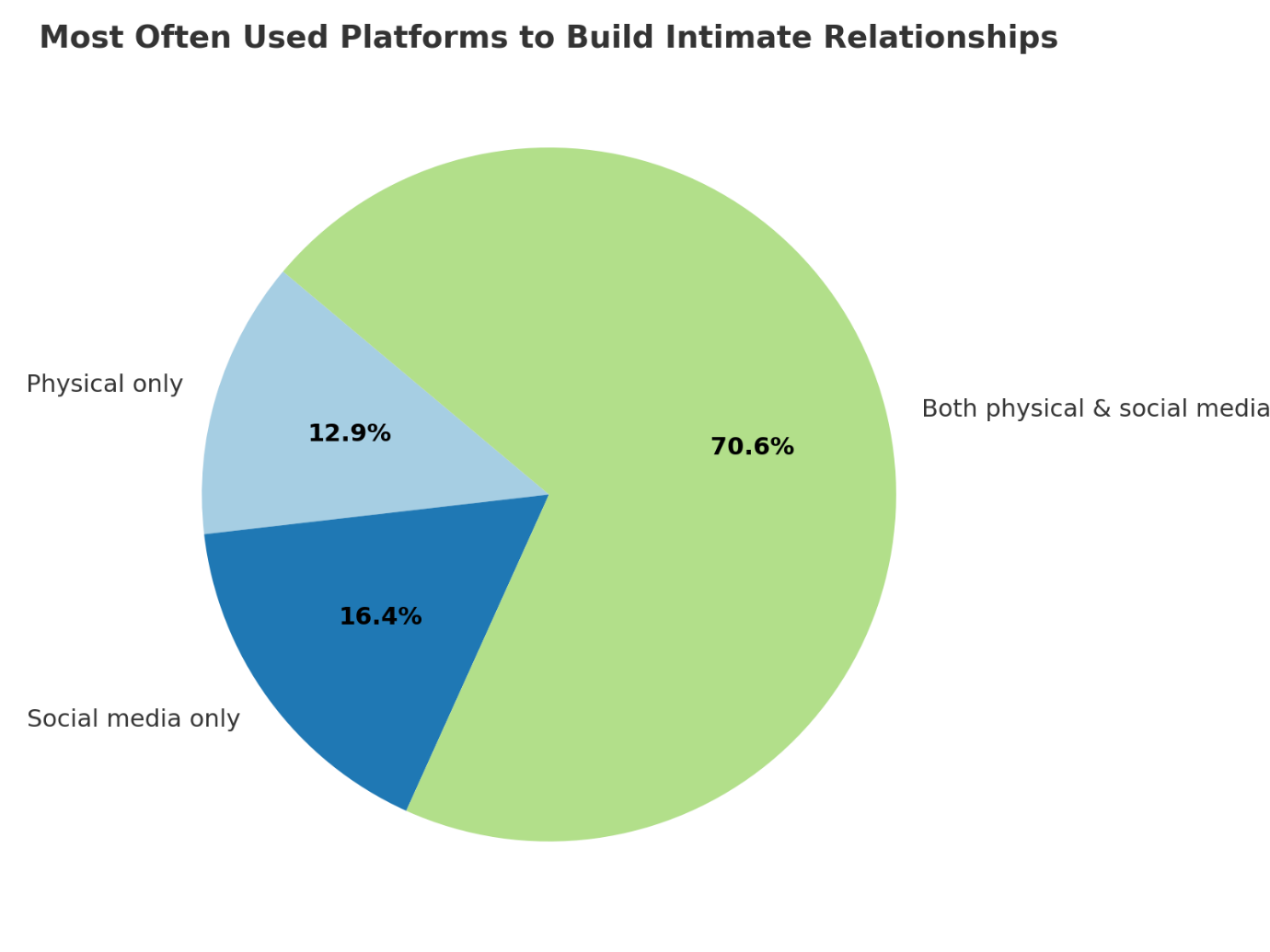

The survey found that 71% of participants seek intimate partners both online and offline, while 16% use mostly social media and 13% prefer physical venues. Most youths combine these approaches for relationships. WhatsApp is the top preferred social platform (55%), followed by Instagram (20%) and Facebook (11%), consistent with its popularity among South African social media users. [22]

Themes derived from the qualitative data gave insights of the quantitative data explaining the patterns of behaviour of participants in relation to building a relationship through online dating as well as social media platforms.

The preference of participants for social media over online dating apps (ODA) may be based on the familiarity that many social media platforms (SMP) such as instant messaging apps (IMA), social networking service (SNS), video-sharing platforms (VSP) and video games (VG) give youth. This familiarity stems from easy access, as most are free,[23] and users can easily navigate within and between social media platforms to form an integrated social media system (ISMS) [24]. Within ISMS, for example, a user can generate content consisting of a personal video and send to a contact on WhatsApp (an IMA). The content receiver may decide to share this video with their contacts by posting it on Facebook (a SNS). Their contact, on receiving this video, may again decide to re-share the video on YouTube (a VSP) or with an online contact they met through an ODA. However, unlike many social media platforms which are free, the generation of user content through ODAs may be more restrictive because most ODA premium licenses come with fees. Not only will social media usage be more than ODA, Danielsbacka et al. indicate that most ODA users are more mature, educated and with higher income than most members of their society.[25]

Several participants affirmed the quantitative findings, stating they neither use nor know anyone who uses ODA. Many claim that they mainly hear about online dating as a phenomenon from news and social media. From these channels, they are exposed to stories suggesting that online dating is risky and serves as avenues to meet “bad people” like ex-convicts, syndicates, serial killers and catfishing. For UA3, a Black South African female:

People […] put themselves in danger by talking to someone who possibly isn't even that person that they think they're talking to […] for all she knows, while on an online dating app she is talking to an ex-convict.

This perception is further fuelled by the possibility of meeting strangers, who emotionally and psychologically manipulate their victims into traps. The belief that ODAs are dangerous is further supported by the narratives given by friends and relations. Harrowing stories of attempts at physical assault, mugging, rape, kidnapping and murder are provided as personal reasons why some participants decided they cannot expose themselves to such risks.

UA9, a Black South African female recounted the “tragic” story of her friend who got mugged when he physically met an online contact:

[He] came back phoneless, shoeless and they wiped out his bank accounts. They asked him to transfer all the money he had left on his iPhone. They took the New Balance shoes he was wearing.

There were also personal accounts given by participants of their experiences when on ODAs. Members of the LGBTQ+ community were especially traumatised by contacts who were only interested in exchanging sexually intimate photos and not in developing any personal relationship with them.

UB9, a Black South African male who is a member of the LGBTQ+ community attempted to capture this through his experience with Grindr, an online dating platform:

It's very common for other males to […] coerce you to send photos […] naked photos of yourself or videos. And they normally do that by sending you theirs without asking for your permission, without even saying “Hello. Hi. What's your name?”, you know. In expectation that you will also do the same. And if you don't do the same, then it goes to cyberbullying.

UB9 also highlighted the hostility of members of society who deliberately create fake profiles to lure them into physical meetings, only to harm them because of their sexual identities. He supported this with a personal experience:

Two years, three years ago, I met this person who sent me his photos. So, upon meeting that person, I realised this is not the person that I was talking to online, you know, […] it was actually a planned […] kidnapping of some sort […] and I had to run away. [...] It was traumatising.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, some participants believe that ODAs will still be a major game changer for South African youths. This is because many South African youths have difficulties physically approaching individuals directly to initiate a relationship. The attraction of privately meeting someone online is still an alluring feature that South African youths will aspire for.

AB6, a Coloured South African captured this as follows:

Young people want to go into the dating world, but they do not want to approach one another. So, the easiest way to do this is by approaching one another on platforms that hide their privacy.

The possibility of ODAs gaining more popularity is supported by the reservations some participants indicated of social media platforms (SMPs), believing that its features make TFGBV more likely. The fact that people can easily access SMPs and form an integrated social media system (ISMS) means TFGBV can be easily committed.

In relationship building, research highlights the importance of SMPs to youths for initiating, sustaining and even terminating a relationship. Within these phases, TFGBV can be committed.[26] Participants characterised the TFGBV committed through SMPs as mainly word-based through negative words associated to posts, videos and pictures, openly and anonymously. Fake or real SNS profiles on SMPs are used to send vulgar, threatening and hateful content without accountability or hindrance across the ISMS. Participants feel more vulnerable when exposed to such TFGBV because perpetrators can easily research their victims while victims do not know their perpetrators. Many participants complained that SMP owners do very little to protect victims who report TFGBV, making some participants to believe the privacy statement often provided by SMP owners are more beneficial to perpetrators than victims.

TFGBV associated with ODA and SMP

The study examined patterns of TFGBV on SMPs and ODAs, comparing current social media users with former dating app users due to few ODA active app participants recorded through the quantitative data. Sexual based violations – such as receiving unwanted flirtatious/sexual messages or unsolicited requests for explicit content – were the most common forms of TFGBV, followed by online stalking. Themes generated through the qualitative responses shed more light about the forms and qualities of the TFGBV experiences of participants on SMP as well as ODA.

Receiving unwanted flirtatious or sexual messages emerged as a major type of TFGBV for participants. They indicated that this was done by other known account users or complete strangers as a way of getting attention to initiating a relationship. To do this, perpetrators would send content that included pictures of private genitals (nudes) or send private requests on SNS. When participants ignore these requests, perpetrators may begin to harass them with continuous messages demanding attention. These constant messages, sometimes sent through different social media platforms within the participant’s ISMS, lead to victims being stalked.

WB7, a Black South African Female spoke of her personal experience:

… On my Instagram page. I have been receiving pictures from people … like disgusting pictures of their private parts and stuff.

Participants reported that these stalkers would pop up on all their social media platforms, with some reporting that some stalkers take the surveillance offline and harass them physically. Participants narrated these patterns of TFGBV as personal experiences as well as experiences of people close to them.

VA8, a Black South African female recounted:

At first (it) started out, […] the guy would take my pictures, post them, and be like, “this is my person.” And I didn't know anything about that. And […] like it got to a point where he even got my contact details, and he would call every day and all that […] until it got to a point where it was like, now I am no longer online. Like I would see him everywhere I go.

There were also cases of impersonation, whereby personal details of someone close to them were taken to create a fake SNS account. Within the cloned account is a fictional persona very different from that of the original account holder. However, most often the original account owner is unaware of the cloned account, but their contacts continue to assume that the account still belongs to the original owner.

Other forms of TFGBV recounted were less frequent, such as doxxing, where original private information of a victim is posted by the perpetrator and tagged to the victim’s contacts. With this act, contacts associated with the victim will believe that there is a strong connection between them.

UB5, a South African Black female recounted:

One time I was just scrolling on my [Facebook] page. I saw someone had posted [my sister] and said that she was looking for marriage and left her contacts there. […] It was more of […] the person being vengeful, you know?

There are also cases of perpetrators taking the pictures of their victims and superimposing them on pornographic images. AA2, a South African Black female shared:

I had a friend who one of the guys in my class used her face to create, like, pornographic photos, even though it wasn't her. So, he just plastered her face with these random bodies, and he uploaded them on social media. So, she had to report him so that it could be taken down. He took her picture without her consent.

And, finally, there were cases of SNS hacking where perpetrators gained access to victims’ account and sent messages to their contacts. AA8, a Black South African female shared:

I have an Instagram account and […] I don't even know how a stranger just happened to get my password. And they took the account, and they put on there that I am their girlfriend. […] I did have a strong password.

Online dating and social media use among LGBTQ+ community

Several of the TFGBV experiences encountered through ODAs were recounted by members of the LGBTQ+ community. Participants that represent this marginalised group indicated that they fear expressing and revealing their true sexual identities to their society because many of them come from backgrounds where such identities are not acceptable nor recognised.

NH9, a Black male member of the LGBTQ+ community explained:

From the LGBTQI perspective, most of us tend to […] search for love in dating apps just because some people [...] inasmuch as people are free of living their lives to the fullest, but [...]some prefer their life private.

This prompts them to turn to SMP to express their sexuality and to ODA for intimate partners. On ODA, participants who represent the LGBTQ+ community recounted experiences of exploitation and violations from older married men.

NH9, a Black South African LGBTQ+ male explained:

To us people of LGBTQI+ [...] the perpetrators are mostly loaded guys, the one with money. Secondly, unhappy married men. […] I've have experienced that, […] a married man going with his family […] only to find out that he's not happy. […] He comes to you. [...] It'd be like, “I'm living a lie. I've been married for six years now. This is not the life I wanted. I just discovered myself.” What happens if that person comes to you as a person who's still growing up? [...] You'd be like, “Oh, I just found a mature guy.” No, that's not it. He's there to destroy you just because his life has been destroyed.

Another participant described his experience of being sexualised or blackmailed with threats from a perpetrator of releasing their intimate pictures to the public. According to NH9:

In search of love, I would […] explore on the dating apps. That's where you encounter many problems. […] You are talking to the person [but] it's not the person you think he is. […] And then the conversation goes well, you exchange pictures, […] that's going to haunt [you] because the person will be manipulating you with those pictures. […] As an individual, you're about to be exposed. […] You'd be like having suicidal thoughts.

Motherhood and online dating

Traditional stereotypes about single mothers create avenues for TFGBV. Being a single mother and looking for an intimate relationship online come with stereotypes shaped within patriarchal gender-based ideologies. Participants indicated that such single mothers experience not only frustration at the notion that a woman with a child should want an intimate partner, but also the vulnerability that comes with exposing this detail through an ODA. This often attracts misogynistic and derogatory comments from some male ODA account holders.

VB8, a Black South African female who is also a single mother expressed her frustration:

There is a stigma that once you are a mother, you are desperate to find a man […] but you're not looking for someone to be a stepfather to your child, but you're just looking for an intimate relationship […] which makes you more […] exposed to things that you're not supposed to be exposed to. [...] I had an experience with someone [who] told me there is no way he's going to marry someone with a child because that was below his standard.

Black women and online dating

Within participant responses were hints of the fetishisation of the Black African woman’s body. These speak to the historical dehumanisation and sexual exploitation of the Black female body; a phenomenon which has roots dating back to the era of European exploration of Africa, a continent described as “virgin” and “uncivilised”,[27] reinforcing the feminisation and sexualisation of the Black African female body as a commodity.[28] European narratives, supported by distorted scientific claims, legitimised this notion especially during the slave trade era and the subsequent colonisation of African land and resources.

Within this context, Farley argues that race operates not merely as a marker of colour but as a mechanism for producing pleasure, where the Black female body is appropriated to satisfy racialised desires across what Farley calls “colour lines”.[29] These fetishised desires, he notes, are both sadomasochistic and masochistic in nature, enabling the economic and political exploitation of the Black female body. Through the positionality of slave owner or colonial master, the white man’s domination was both normalised and legitimised.

In South Africa, Schyff draws attention to the case of Sara Baartman, whose body was dissected and displayed as an emblem of colonial racism, sexism and domination.[30] In contemporary times, the enduring positionality of white men – shaped by power, privilege and material advantage – may have created new avenues for which SMPs can become sites for the manifestation of these evolved fetishised desires.

For AB7, a Black South African female, who identifies as a victim of fetish-related TFGBV from white male ODA account holders, indicated that she often gets messages from White men who express their desire to “experiment” with a Black woman because of her body shape. The desire to feel, for example, “if my bum is real,” illustrates what participants identified as the white male fetish to be with a Black Woman.

AB7, a Black South African female recounted her experiences with online dating:

I have personally experienced […] on an online dating app […] white men wanting to be with Black women, and they would actually say such offensive things like, “I just want to experiment what it's like being with Black women. I just want to feel if your bum is actually real.” So those offensive kinds of conversations come across a lot on dating apps.

Positive and negative emotions from social media interactions

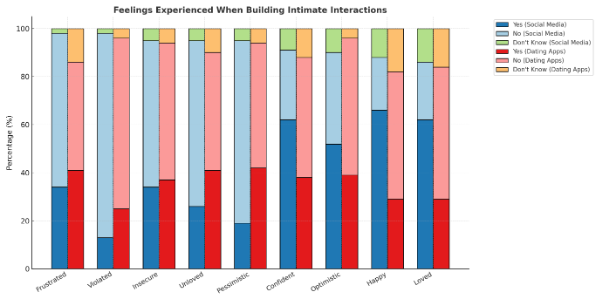

The study attempted to understand the impact of negative and positive emotions that TFGBV can cause when encountered through SMP and ODA. By comparing SMP users with past ODA users, it was expected that due to the limited physical interactions the ODA users had with their contacts, as well as the limited time they spent in communication with their contacts, there would be more negative feelings expressed when compared with other social media users who have more access due to the ISMS. This question aimed to understand more of participant’s personal feelings resulting from SMP and ODA interactions.

Studies indicate that these interactions can cause positive as well as negative emotions.[31] The study aimed to understand the more prevalent of these emotions and qualify them.

From the quantitative data, feelings of insecurity and frustration were identified as having the closest mix of positive and negative emotions experienced through SMP as well as ODA. This is followed with emotions related to feeling unloved, pessimistic and violated. More obvious positive emotions include being optimistic, confident, happy and loved when interacting on both SMP as well as ODA.

Qualitative themes that emerged from the FGD gave more depths to the negative and positive emotions participants experience when interacting with contacts on SMP as well as ODA.

Frustration was an intense negative emotion felt by participants especially at the termination stage of a relationship. This frustration is presented by participants as an emotion directed at the self and expressed as anger, shame, loneliness and feeling unheard because of TFGBV experiences.

NH3, a Black South African female stated:

I think the anger that you have towards yourself, that you put yourself out there and you feel like it's your fault that everything that's happening is happening the way that it is because of yourself and the decisions you took.

This is followed by feeling unloved and insecure. This was captured by participants when they receive harsh and insulting words from strangers and intimate partners, especially at the initiation and exiting stage of relationships. When asked to describe some of the emotions they felt when they encountered these diverse forms of TFGBV, some participants indicated that they just stopped talking to people or went off social media completely.

AB1, a white South African bisexual male who encountered online insults at the edge of his breakup:

With the individual I spent about ten years with, I went into about a type of social media remission for a year. I completely lost all activity online. I stopped talking to a lot of people. […] This was mostly just mental and emotional stuff.

The process sometimes led to mental and emotional reclusion, while others physically hurt themselves as they relive the abuse.

VA4, a Black South African Female explained from her experience why this can be so detrimental:

[I] will be looking at the message, […] focusing on whatever you said. Even if I report or delete it, it's still considered violence, […] any form of violence I faced, any trauma I faced. I used to have scars and some of them are still visible. Whenever I'm alone, I would blame myself for whatever they said or whatever they did. And I would take maybe a knife or something sharp just to give myself scars, thinking that it might be some form of healing because I'm not the type to be talking.

They became insecure of themselves online and refused to post or generate any content reflecting themselves. Within themselves, some indicated that they felt anger, hate for the perpetrator, felt disrespected and disgusted with themselves for being so vulnerable and easily deceived.

UB7, a Black South African female captured this feeling:

I think shame and fear. […] I mean[...]I feel like also some lack of respect as well. You feel like the person does not respect you. And I feel like hate. Hatred for the person comes very late. You mostly scared, you are mostly ashamed, you mostly panicking and all that. And you hate yourself more than you hate that person.

UB9, a Black South African male member of the LGBTQ+ who experienced the sexualisation of his body online from an online contact explained:

I can't talk about other people, but myself, it really hurts my self-esteem. So, I feel self-hatred, you know, in a way. It feels like I have no worth. You know, my worth is being attached to a nude photo or video or something like that.

Some indicated that they became pessimistic about the possibility of ever building positive relationships as they developed a sense of distrust for people both online and offline.

UA3, a Black South African female pointed out:

It (negative emotions) doesn't even have an immediate [...] reaction. But some people's comments like stick to you. So, it affects how you view yourself long term. It affects how you deal with life. [T]o a certain extent you internalise it. […] It affects […] your confidence as a female or as a male or non-binary, etc. […] It affects your decisions.

More positive emotions were captured by participants who recounted being happy because of the relationships they built through SMP, indicating relationships with people across the globe. There were also accounts of feeling happy that there is someone they can turn to and relay both good and bad occurrences in their lives without the judgement or vile criticism from people around them. The anonymity that SMP gives them, allows them to create a persona that may not coincide with their real one. For example, if they are naturally shy, they can decide to present themselves as very extroverted to their ODA contact.

VB8, a Black South African female, explained:

You get to choose how you portray yourself to that person, […] if maybe I'm a very straightforward person. I know that. But I can choose to tell that person that I'm a very shy person. I'm reserved. […] It could all be a lie […] as much as it is a bad thing for the other person, it can be an advantage for me as the person who's doing it because I want to look nice.

As long as the relationship is kept online, participants indicate they have peace of mind. For other participants, it is the confidence ODA and SMP give them to approach people they normally may not be able to physically. For male participants, this is a game changer as they can be bold, not afraid to be seen as boring or unromantic, while spending less resources.

MA2, a Black South African male explained:

Building a relationship online […] helps in understanding a person before going to them, because [...] many of us, we don't always approach women personally. It’s better for us to approach online, to get to know each other more. […] Now you have that confidence […] because women will say, when you [meet physically], you are too boring, […] you must be trying to be romantic.

There were also stories of platonic relationships built over SNS, some as old as two years without seeing each other physically. Some participants also indicated that their current intimate relationships were initiated through an SNS platform.

Responses and reactions to TFGBV as perpetuated through social media apps

The research attempted to understand the responses and reactions of participants to TFGBV as perpetuated through online SMP and ODA. The quantitative survey indicated that respondents are less likely to share their online negative experiences. When asked if they shared their negative online experiences with anyone, 53% indicated that they did not, while 45% answered in the affirmative. When asked who they would likely share these experiences with, 64% indicated friends, colleagues or peers; 24% family members (parents, siblings or extended family); 9% a professional body (for example, a legal practitioner, psychologist or public official); and 3% a member of the university council or other bodies of authority. More respondents, however, were more likely to share their positive experiences (69%) than their negative ones.

To give more insights into the formal under-reporting indicated in the quantitative data, themes from the qualitative responses were analysed. Participants indicated that their fear of social judgment because of their search for love or desire to build a relationship online as a major reason for not reporting their experiences of TFGBV. The fact that the older generation has not yet come to terms with the possibility that real relationships can be developed online was perceived by respondents as the major root cause of under-reporting. Participants indicated that they would be asked questions as to why they could not physically look for love.

WA1, a South African Black female explained:

People usually do not talk about them, […] they keep it to themselves. [P]eople are afraid to talk about it because […] in society, you can be judged, […] what were you doing looking for love on social media? Why didn’t you look for it here, […] right here in front of you?

These are believed to be the queries they will get when they attempt to report incidents of TFGBV. This is made worse by the fact that many of the participants confessed that they do not even know the terms to define the TFGBV they were facing. Their limited understanding of TFGBV makes it difficult for them to describe the crime or provide evidence for further investigation.

UB7 a Black South African Female explains the trauma of reporting TFGBV:

You don't know [...] who the person is. […] You don't know their address. You don't know their details. You just have their social media handle. And that is not much to go on. You can't go there and [say] this is where I can find them. […] I don't know what to say […] when we go to the police station.

This makes them afraid of being mocked, especially members of the LGBTQ+ who already face social victimisation.

Finally, is the perception that law enforcement agents are not trained to fight online crime. They can physically act against physical crimes related to GBV as a lot of campaigns against this have been made by the government. Thus, GBV crimes such as rape are familiar terms for law enforcement officers. However, crimes such as non-consensual dissemination of intimate images or other sexual related TFGBV crimes seem insignificant. Participants felt the law reinforcement might tell them that it is not a serious crime, and they will be told to “switch off your phone” or “block them,” and thus nothing will be done to follow up on the matter.

UB7, a Black South African Female stated:

Our justice system is really poor […] for online [crimes], because you're going to report an account or […] a person behind an account, so you are at risk of being told that it's not that serious, it's not that deep. You can just block them and move on. […] I feel like they don't know what to do and as a result they end up not doing anything.

This makes participants feel they will undergo secondary victimisation while the perpetrators get away. Thus, when they encounter TFGBV, they often keep the crime to themselves and block the perpetrators from having access to their ISMS. However, because social media is so integrated, some perpetrators come back to torment their victims using other social media platforms or through fake accounts and profiles. This forces the victim to go off social media completely thereby silencing them and reducing their right to express themselves and be a part of the social media world.

Conclusion

Through a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies, this research analysed patterns of TFGBV affecting South African university youth via social media and online dating platforms. The quantitative findings revealed limited engagement with ODA, while qualitative data illuminated contributing factors for this trend to include negative reports from media, family and friends, including incidents of attempted mugging and homicide, and concerns regarding the anonymity of online interactions.

Respondents highlighted that social media, particularly SNS like Facebook and Instagram, serve as the predominant channels for emotional forms of TFGBV, including the dissemination and sharing of adverse comments and posts. A key finding was the prevalence of sexually explicit message generation and distribution, often occurring at the outset of relationships, manifesting as requests for or unsolicited transmission of “nudes”.

For minority groups, notably LGBTQ+ members, incidences of TFGBV were closely linked to their identities – encompassing student status, youth and financial vulnerability. Similarly, single young mothers seeking intimate connections sometimes became victims of misogynistic remarks targeting their social positioning. Black female participants described receiving fetishist comments rooted in the sexualisation of their bodies.

Relationship formation stages, particularly initiation and dissolution, were associated with heightened aggression in TFGBV occurrences. These interactions significantly influenced users' emotional states on SMP and ODA, with the quantitative data indicating varied emotional responses. Qualitative insights further elaborated on these experiences, revealing themes of happiness, insecurity, pessimism and frustration, as well as positive emotions such as feeling loved, optimistic, happy and confident – reflecting the nature of online engagements.

Furthermore, many participants indicated they would not disclose negative experiences from online interactions to wider audiences, preferring to confide in friends, peers or colleagues rather than older individuals and people in authority. Qualitative analysis suggested that this reluctance stems from fears of social judgment and a perceived inadequacy of law enforcement agencies in addressing internet-based crimes. Consequently, perpetrators often go unpunished, while victims may experience secondary victimisation.

Recommendations

South African youth need platforms where they can safely report their experiences of TFGBV to the society, and law enforcement agencies more specifically. They also need platforms to share their stories to encourage other victims who may not have the voice or courage to speak out.

Law enforcement agencies need to be trained about TFGBV, and work with ICT companies to keep abreast of the ever-changing, evolving and innovative world of digital technology. In addition, laws must be put in place to punish TFGBV perpetrators, and to educate them of the harm they cause. As one participant noted, if victims are not aware that TFGBV is a crime, it is possible some perpetrators are also not aware. They may see their actions as a joke and not a torment.

Once boundaries are set, both possible perpetrators as well as victims will know there are consequences for actions that harm individuals, whether offline or online. These laws must also be adhered to by social media operators, to enforce them to take responsibility for protecting users and ensure that their user-generated content is safe and not harmful to themselves or to other users.

Finally, more education and awareness must be done to educate all stakeholders – including government, higher education authorities, account holders, social media owners and operators – of the harm TFGBV can cause. The fact that such violence happens online does not make it a less harmful or insignificant violation of rights and dignity.

Footnotes

[1] MXit was a pioneer mobile instant messaging app in South Africa. It was launched in 2006.; Chigona, A., & Chigona, W. (2008). MXIT it up in the media: Media discourse analysis on mobile instant messaging system. The Southern African Journal of Information and Communication, 9, 42-57. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA20777213_49; Samie, N. (2011, 18 October 18). Social media popular with South African youth. VOA News. https://www.voanews.com/a/social-media-popular-for-south-african-youth-…

[2] Mbodila, M., Ndebele, C., & Muhandji, K. (2014). The effect of social media on student’s engagement and collaboration in higher education: A case study of the use of Facebook at a South African University. Journal of Communication, 5(2), 115-125; Wiese, M., Lauer, J., Pantazis, G., & Samuels, J., (2014). Social networking experiences on Facebook: A survey of gender differences amongst students. Acta Commercii, 14(1), 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v14i1.218

[3] Matenda, S., Naidoo, G., & Rugbeer, H. (2020). A study of young people’s use of social media for social capital in Mthatha, Eastern Cape. Communitas, 25, 1-15. https://dx.doi. org/10.18820/24150525/Comm.v25.10

[4] Sherma, H. & Mahajan, S. (2024). Social media and relationship dynamics: Exploring the impact of usage patterns on trust, jealousy, and overall satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Medical and Dental Research, 12(2):5-7. https://www.jamdsr.com/uploadfiles/2vol12issue2pp5-720240213085950.pdf; Langlais, M., Boudreau, C. & Asad, L. (2024). TikTok and romantic relationships: A qualitative descriptive analysis. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 8(3), 95-112. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/14896

[5] Matook, S. & Butler, B. (2015.) Social media and relationships. In R. Mansell and P.H. Ang (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://10.1002/9781118290743.wbiedcs097; Zhu, Y. (2025). Anonymous intimacy in the digital age: Psychological mechanisms, risks and potential. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Research in Social Sciences, 2(1), 11-29. https://10.33422/icarss.v2i1.1056

[6] Davids, N. (2024, 3 December). ‘Yes GBV manifests through online platforms too’. University of Cape Town News. https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2024-12-03-yes-gbv-manifests-throug…

[7] Hinson, L., Mueller, J., O’Brien-Mine, L., & Wandera, N. (2018). Technology-facilitated gender-based violence: What is it, and how do we measure it?. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW). https://www.svri.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-07-24/ICRW_TF…

[8] Rasool, S. (2017). Adolescent reports of experiencing gender-based violence: Findings from a sectional survey from schools in a South African city. Gender & Behaviour, 15(2), 9109-9120. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-b4170923f

[9] Matenda, S., Naidoo, G., Rugbeer, H. (2020). Op cit.; Chigona, A., & Chigona, W. (2008). The use of mobile phones to support informal learning.

The Journal of the Institute for African Development, 5(1), 1–17.

[10] Davids, N. (2019, 10 November). Gender-based violence in South African universities: An institutional challenge. Council on Higher Education. https://www.che.ac.za/file/6459/download?token=XT7N1ToO; Mdletshe, L. C., & Makhaye, M. S. (2025). Suffering in silence: Reasons why victims of gender-based violence in higher education institutions choose not to report their victimization. Social Sciences, 14(6), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060336; Mabaso, K. & Ndlovu, M. (2019). Womxn university students’ narratives of gender-based violence through digital storytelling. Thesis submitted to the Department of Psychology, University of Cape Town. https://humanities.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/content_migration/huma…

[11] Statista. (2025). Distribution of social media users in South Africa as of January 2024 by age group and gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1100988/age-distribution-of-social-…; Lukose, J., Mwansa, G., Ngandu, R., Oki, O., (2023). Investigating the impact of social media usage on mental health of young adults in Buffalo City, South Africa. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 6(6), 303-314. http://dx.doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v6i6.1365

[12] Bosch, T. (2022, 6 April). The dating game: survey shows how and why South Africans use Tinder. University of Cape Town News. https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2022-04-06-the-dating-game-survey-s…

[13] Basson, A. (n.d.). ‘New media’ usage among youth in South Africa. Gender & Media Diversity Journal, 136-142. https://genderlinks.org.za/wp-content/uploads/imported/articles/attachm…; Mutongoza, B., & Hendricks, E. (2023). Technology-enabled gender-based violence: Students’ experiences at a university in South Africa. Paper presented at the Social Sciences International Conference, October, Umhlanga, South Africa.

[14] Davids, N. (2019, 10 November). Op cit.

[15] McInnes, K. (2025, 20 March). South African Digital & Social Media Statistics. Meltwater. https://www.meltwater.com/en/blog/2025-social-media-statistics-south-africa; Amaechi, K. (2024). A resource mobilisation study of how Facebook enables gender base violence in the online space in South Africa. Gender and Behaviour, 22(1). https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-genbeh_v22_n1_a8; Opoku, S., Badu, E., & Kwame, P. (2025). The danger of online dating among university students in the Kwazulu Natal Province, South Africa. Paper presented at the 8th World Conference on Research in Social Sciences, 21-23 February, Milan, Italy. World Conference on Research in Social Sciences. https://www.dpublication.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/04-3761.pdf; Rutgers International. (2024). Decoding technology facilitated gender-based violence: A reality check from seven countries. https://rutgers.international/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Decoding-TFGBV…; Mutongoza, B., & Hendricks, E. (2023). Technology-enabled gender-based violence: students’ experiences at a university in South Africa. Paper presented at the Social Sciences International Conference, October, Umhlanga, South Africa.

[16] Bosch, T. (2022, 6 April). Op cit.

[17] Opoku, S., Badu, E., & Kwame, P. (2025). Op cit.

[18] Bhana, D., Reddy, V., & Moosa, S. (2024). Young people becoming intimate on social media: Digital desires and gender dynamics. Sexualities, 28(4), 1653-1670. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607241281449 (Original work published 2025).

[19] Bhana, D., Reddy, V., & Moosa, S. (2024). Op cit.; Citron, D. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace: Introduction. University of Maryland Legal Studies Research Paper, 11, 1-12. Harvard University Press. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2616790; Chen, T. (2025). The new patriarchal digitality? Understanding gendered power dynamics through a systematic review of femtech apps in China. Gender, Technology and Development, 29(2), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2025.2503561; Irish Consortium on Gender Based Violence. (2023). Technology and gender-based violence: Risks and opportunities. https://www.gbv.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/CSW67-Technology-and-Gend…; ESafety Commissioner. (2025). Impersonation, catfishing and identity theft. https://www.esafety.gov.au/lgbtiq/learning-lounge/meeting-online/impers…; Nyamweda, T. (2021). Understanding online gender-based violence in Southern Africa: An eight country analysis of the prevalence of digitally enabled gender-based violence. Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria. https://www.chr.up.ac.za/images/researchunits/dgdr/documents/resources/FINAL_v_Understanding_oGBV_in_Southern_Africa.pdf; Nduko, M. (n.d.). Online violence against women, rape culture and the South African Manosphere: The potential of the SADC protocol; on gender and development. Africa Legal Aid. https://www.africalegalaid.com/online-violence-against-women-rape-culture-and-the-south-african-manosphere#:~:text=While%20gender%2Dbased%20violence%20(GBV,new%20avenues'%20for%20its%20perpetration

[20] Rutgers International. (2024). Op cit.

[21] South African Government. (2025). Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013. https://www.gov.za/documents/protection-personal-information-act#:~:tex…

[22] McInnes, K. (2025, 20 March). Op. cit

[23] Manning, J. (2014). Social media, definition and classes of. In K. Harvey (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Media and Politics. Sage. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290514612_Definition_and_Classes_of_Social_Media

[24] Wolf, M., Sims, J., & Yang, H. (2018). Social media? What social media? In UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2018. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2018/3

[25] Danielsbacka, M., Tanskanen, A. & Billari, F. (2019). Who meets online? Personality traits and sociodemographic characteristics associated with online partnering in Germany. Personality and Individual Differences, 143(1), 139-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.024

[26] Langlais, M., Boudreau, C. & Asad, L. (2024). Op cit.; Courtice, E. L., Czechowski, K., Noorishad, P. G., & Shaughnessy, K. (2021). Unsolicited pics and sexual scripts: Gender and relationship context of compliant and non-consensual technology-mediated sexual interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 19(12), 673202. https://10.3389/fpsyg.2021.673202; Bhana, D., Reddy, V., & Moosa, S. (2024). Op cit.; Sherma, H. & Mahajan, S. (2024). Op cit.; Orben, A., & Dunbar, R. (2017). Social media and relationship development: The effect of valence and intimacy of posts. Computers in Human Behaviour, 73, 489-498. https://10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.006; Nguyen, T. (2025). The association between social media use and romantic outcomes: A scoping review. Master Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Behavioural Management and Social Sciences, Positive Clinical Psychology & technology, University of Twente. https://essay.utwente.nl/104912/1/Nguyen_MA_BMS.pdf

[27] Khamseh, L. (n.d.). The fetishization of African American women in the Hip-Hop industry and its relation to cultural appropriation. Bachelor’s thesis, American Studies, Radboud University. https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/server/api/core/bitstreams/7741fcc4-d138-4b53-92d9-bf967735cf17/content

[28] Holmes, C. M. (2016). The Colonial Roots of the Racial Fetishization of Black Women. Black & Gold, 2. https://openworks.wooster.edu/blackandgold/vol2/iss1/2

[29] Farley, A. (1997). The Black body as a fetish object. Oregon Law Review, 76(3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228199678_The_Black_Body_as_Fetish_Object

[30] Schyff, K. (2018). Beyond the “Baartman Trope”: Representations of Black women’s bodies from early South African proto-nationalisms to postapartheid nationalisms. Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Language and Literature, University of Cape Town. https://share.google/xG59lHBfjeZIrB0iG

[31] Bengtsson, S., & Johansson, S. (2022). The meanings of social media use in everyday life: Filling empty slots, everyday transformations, and mood management. Social Media + Society, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221130292 (Original work published 2022).

- 87 views

Add new comment